Mayo stories reveal strangeness of life in post-Soviet Lithuania

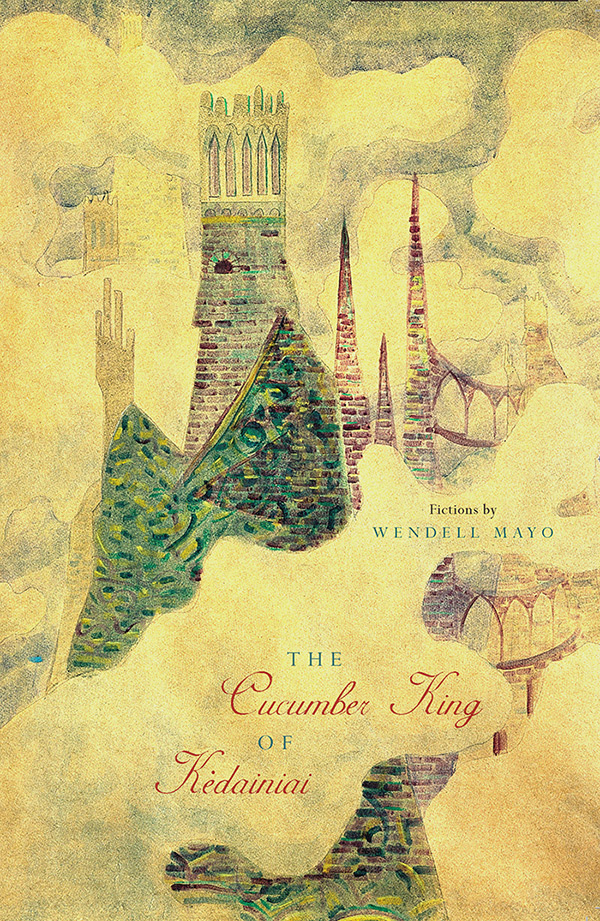

BOWLING GREEN, O.—Wendell Mayo is not Lithuanian, but the Baltic country has occupied his thoughts, his summers and his writing for nearly 20 years. His latest collection of short stories, “The Cucumber King of Kedainiai,” presents six acute vignettes of contemporary life in the former Soviet republic, where the past way of life is gone, the new way is unsettled, and in some ways there is, Mayo says, “a horrible sense of absence,” even for a cucumber king.

The collection was published in October by Subito Press, of the University of Colorado at Boulder, and won the Subito Press Award. Mayo has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1996. A full professor, he has a Master of Fine Arts in fiction writing from Vermont College and a Ph.D. in English from Ohio University.

The protagonist of the title story is a real personage, a sort of Mafia overlord of the country’s important pickle industry. In Mayo’s fictionalized version, the reader shares the narrator’s dislocation and dreamlike perception at finding himself in the castle of the cucumber king, where a tour through the endless rooms reveals most of all an overarching emptiness, everyone beside the king having decamped to brighter shores.

The protagonist of the title story is a real personage, a sort of Mafia overlord of the country’s important pickle industry. In Mayo’s fictionalized version, the reader shares the narrator’s dislocation and dreamlike perception at finding himself in the castle of the cucumber king, where a tour through the endless rooms reveals most of all an overarching emptiness, everyone beside the king having decamped to brighter shores.

A sense of the absurdity of life in post-Soviet Lithuania pervades the stories, giving them a melancholy and dark humor. In “Brezhnev’s Eyebrows,” a painter hopes the money from the sale of a portrait will convince his disaffected wife to stay. In “Cold Fried Pike,” a grandmother recalls the deaths of her father and brothers at the hands of the KGB, while methodically eating a gifted fish.

Despite the country’s struggles, Mayo was drawn to the culture, saying, “I’m a sucker for courage.”

He was impressed by the fact that Lithuania was the first Soviet republic to declare its independence. Even when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev ordered tanks into Lithuania to crush the resistance and 13 protestors were murdered, even when the border patrol shot dead eight people and Gorbachev turned off the country’s natural gas, Mayo said, “Lithuania stood fast,” adding he thought at the time, “I really should meet these people.”

Mayo’s first book about the country, “In Lithuanian Wood,” published in 1999, reflects the “sudden welling-up of a desire for independence and freedom,” he said. “The Cucumber King” sees Lithuanians in the globalized present, where “in a country formerly of 3.7 million, 700,000 have moved away and are not coming back,” Mayo said. “Half of that drop has happened in the last two years. There’s a tremendous brain drain.”

Those left behind are in the strange position of having to learn to do things most of the rest of the world takes for granted. “Every aspect of life has changed” with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Mayo noted. His landlady, a nationally famous soap opera star, asked him to help her write checks to pay bills, never having had to do such things before. “How could I not be fascinated?” he said.

Part of his reason for writing the books, he said, “is for people who can’t go to their country of origin.” And telling stories is a universal way of creating a bond between people, he observed, something he experienced while living in Lithuania.

The many years of oppression have left Lithuanians “very deep and into themselves, very introverted,” Mayo said. There is lingering resentment against those who were informants for the KGB, despite the fact that most did it simply to earn the money to survive. The paranoia created by having one in five people informing on the rest is a strong presence in the story collection.

“Yet there’s a strong sense of collective identity and suffering,” Mayo said. “When the (Berlin) wall went down, they saw a real opportunity and they were willing to take it. They didn’t care if it meant death.”

Mayo began going to Lithuania at the prompting of his wife, who is of Lithuanian descent, when she saw an ad seeking teachers of English who could help share democratic education methods.

“I went one summer but I had no intention of writing anything about it. I just wanted to help out,” Mayo said. “But I did keep a detailed writing journal, which is unusual for me.”

He continued to return to Lithuania to train teachers through the American Professional Partnership for Lithuanian Education and later as a 2001-02 Fulbright Scholar in the capital, Vilnius. “By the third year I felt I knew enough to write about the American experience encountering the former Soviet culture,” he said.

“There was some cultural misunderstanding the first couple of years,” he noted, on both his and the Lithuanians’ side. Some were suspicious of Americans, seeing them as imperialist. On his part, he realized he needed to have Lithuanian friends proofread his stories after he had a character who had lost his job look through the classified ads for a new one. But, as his Lithuanian reader pointed out, there are no want ads in Lithuania. “If someone loses a job they will be given one. It may not be the job they want or pay well, but there is no joblessness,” Mayo said. “The same is true for housing.”

Mayo said he tries to write honestly about a people who, since liberation, “have learned that freedom isn’t free, and to express how much I admire the country.”

Updated: 12/02/2017 12:50AM