Baron book unearths lost history of today’s Modern acting

dMention American acting styles in conversation and most people will assume you are talking about Method acting. But film historian Dr. Cynthia Baron, theater and film will be quick to point out that the Method made famous by Lee Strasberg and his most famous pupil, Marilyn Monroe, held sway for only a few years and was soon abandoned by most actors.

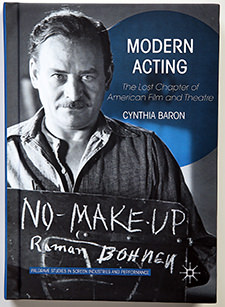

What came before and has endured is Modern acting, which was developed by a number of dedicated teachers and theater companies and reached fruition in the 1930s and ‘40s. Baron’s latest book, “Modern Acting: The Lost Chapter of American Film and Theatre,” introduces us to the form of acting we know today, setting the record straight and giving credit to all those “unsung heroes” who worked mostly behind the scenes to create a style suited to the changing face of drama. Published by Palgrave Macmillan, “Modern Acting” is part of its Palgrave Studies in Screen Industries and Performance series.

In tracing the genesis of what came to be known as Modern acting, Baron found that a number of factors played into the need for a new approach. With the shift to modern life, the style of drama began to change at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. There was much discussion about what kinds of plays were needed for society and for the different nations. Playwrights such as Ibsen, Chekhov and O’Neill came to prominence, and theater spaces and stagecraft adapted to better present the more interior, intimate works. And movies came onto the scene in a big way, especially with the decline of Broadway in the mid-1930s and the migration West of out-of-work actors seeking jobs in radio and film.

“With the expansion of Hollywood in the 1930s and ’40s, film became the key performing art of the United States,” Baron said.

In response, a different style of acting emerged that was appropriate for the new contexts. “This style fit seamlessly into the new vision of drama and staging,” Baron said. “And that’s what has been lost from history.”

Another forgotten piece is that many of the style’s founders were women, she said. While we may recognize some of the names, such as Stella Adler, Maria Ouspenskaya and Eva Le Gallienne, other important figures such as Sophie Rosenstein and Josephine Dillon are virtually unheard of today. (Baron also chronicles the dramatic, pivotal break between Adler and Strasberg that led to the final schism between the two schools of acting and clears up the widely held misconception that Marlon Brando was a Method actor. In fact, he disavowed the Method and Strasberg.)

Baron was also motivated to correct the lost history out of respect for those whose lives were impacted, and sometimes ruined, by the scourge of McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist that unfairly put so many talented actors, writers and others out of work. In fact, the book’s cover is a dramatic black and white photo of actor Roman Bohnen, a leader and guiding force of the Group Theatre and then Actors’ Laboratory Theatre. A victim of the blacklist, Bohnen’s 1949 collapse and death onstage were attributed to the enormous stress he suffered.

“These heartbreaking stories fueled my energy in working on this,” Baron said.

Meticulously researched and richly illustrated throughout with photographs, “Modern Acting” restores these seminal figures to their true place in the history of Modern acting.

The book also connects the work of today’s actors to the very beginnings of this important new style, which has proved so robust that it allows contemporary performers to be effective in not only theater, television and film, but also new media, voice-acting and motion-capture productions — platforms unheard of by those original practitioners.

Unlike the profoundly different Method acting, which relied on directors to control and elicit performances from their actors, who in turn had to look inward to evoke emotional responses to personal memories, Modern acting — based in part on the Stanislavsky system — considers actors as artists in their own right. Modern actors learned to analyze scripts and contexts to create characters whose responses are consonant with those characters’ personalities as well as their times and situations. The actors were also highly trained in using their voice and physical presence to embody the characterizations.

Moreover, when sound became part of movies, actors could no longer rely on directors to guide them through scenes but had to arrive on the set ready to perform, Baron said. A growing professionalism arose, along with a sense of personal and group responsibility as theater companies were founded that were dedicated to the new principles of acting, to social responsibility and to the equality of all their members.

“That effort to be part of an ensemble, to be sensitive to one’s colleagues and really bring your ‘A game’ no matter how small your role — that was impressive,” Baron said. “Likewise, the acting coaches who were willing to be invisible and work in obscurity for the sake of their craft.”

Although until now much of the historical knowledge of the era had been lost, some of those theaters and acting schools still exist. The Pasadena Playhouse, founded as a community theater in 1925 and soon named the State Theatre of California, continues to stage productions. Similarly, the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, established in 1884 and home to actors ranging from Lauren Bacall to Robert Redford, continues to provide training for contemporary talent like Jessica Chastain.

Baron also is the author of “Denzel Washington” (2015) and co-author of “Reframing Screen Performance” (2008) and “Appetites and Anxieties: Food, Film and the Politics of Representation” (2014). She is the co-editor of “More Than a Method” (2004).

Updated: 12/02/2017 12:37AM