Lecture Series

Each year, the Center for Archival Collections hosts several public lectures from speakers on a range of topics encompassed within the CAC's collecting specialties, including the history of BGSU, northwest Ohio, the Great Lakes, American literature, and much more. Most lectures are presented by winners of the CAC's annual Local History Publication Awards, while others are standalone programs highlighting the work of authors, historians, and scholars for whom the CAC's collections have been essential primary sources in their research.

During the lecture series, you will

- Expand your knowledge of the CAC's unique collections and the myriad historical subjects they document

- Engage with experts and peers

- Gather inspiration for your own writing or research

All lectures are free and open to the public.

Upcoming Lectures

Past Lectures

Ralph Lindeman: "Confederates from Canada: John Yates Beall and the Rebel Raids on the Great Lakes" (October 31, 2024)

Author Ralph Lindeman discusses his book Confederates from Canada: John Yates Beall and the Rebel Raids on the Great Lakes (McFarland & Company, 2023), winner of the BGSU Center for Archival Collections' 2024 Local History Publication Award in the Professional Division's Book Category.

David Adams: "'CRONOS' and 'The Golden Goose': Vital Chapters in the History of Post-War Poetry and Publishing" (October 24, 2024)

Poet David Adams discusses his decades-long research into the editorial and publishing histories of the pioneering post-war American literary magazines CRONOS and The Golden Goose, published between 1947 and 1954. Among the founding editors of both publications was Dr. Frederick Eckman, Professor of English at Bowling Green State University and co-founder of BGSU's Creative Writing Program, and under whom David Adams studied as an undergraduate student in the 1960s.

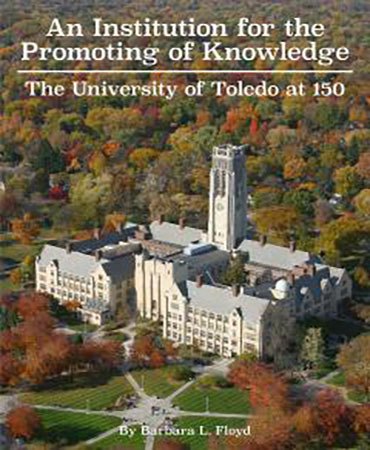

Barbara Floyd - "An Institution for the Promoting of Knowledge: The University of Toledo at 150" (October 23, 2023)

Barbara Floyd, Toledo historian and former director of the Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections at the University of Toledo, speaks about her book An Institution for the Promoting of Knowledge: The University of Toledo at 150 (University of Toledo Press, 2022), winner of the CAC’s Local History Publication Award in the Professional Division's Book Category for the year 2022.

PDF Transcript of "An Institution for the Promoting of Knowledge: The University of Toledo at 150"

Barbara Floyd:

Well, it's really great to be here today. I can't believe all of you turned out to learn about the University of Toledo, but I'm very glad that you did. As I was saying before, it's really great to get awards, but when you get awards from your peers, it means something really special. So I really want to thank the local History Publications Committee for giving me the opportunity to have this award and to give this talk today. So thank you all for coming.

Barbara Floyd:

The 1960s was a watershed decade on college campuses across the United States, and certainly Northwest Ohio was no exception. The decade began with America fully entrenched in conservative political ideas and ended with the adoption of some of the most liberal government policies in our history, many with roots on college campuses. It began with the aftermath of a war in Korea and ended with a war in Vietnam.

Barbara Floyd:

It began with college social life, dominated by frivolous fraternity and sorority rushes and dances and ended with rock concerts and political rallies. It began with college envisioned at a place where men were men to earn their degrees that would allow them to support families and ended with college scenes a way to address society's problems and inequities, including discrimination against minorities and women. It began with students accepting that faculty and administrators made wise decisions on their behalf and ended with them demanding the right to free speech and a say in decisions that affected them.

Barbara Floyd:

The University of Toledo certainly experienced all of these watershed changes, but at UT, the decade was complicated by other factors such as how to rapidly expand its curriculum and physical plant. While still a municipal university supported by the taxpayers of the City of Toledo. The financial limitations of being a municipal institution produced an untenable situation. It would eventually lead to calls by students and their parents for the university to join Ohio's system of higher education to reap the benefits of state supported tuition and capital expansion.

Barbara Floyd:

To administer the rapid change of the 1960s decades, universities demanded leaders who could oversee not only academics, but also government relations, accrediting boards, athletic programs, student services, alumni organizations, fundraising campaigns, construction projects, research programs, and community economic development. The days of college presidents quaintly learning on the job as the Ivy slowly grew up the sides of their buildings were over.

Barbara Floyd:

So let's go back to the beginning of that momentous decade and examine how the University of Toledo served an example of how the historical events of the 1960s changed colleges and universities forever. To do that, it's necessary to examine some of the issues that arose in the decade before. In October 1950, the board of directors hired Asa S. Knowles as the University of Toledo's ninth president following the death of one president and the resignation of another. Both of President Knowles' predecessors had felt the strain of inadequate budgets due to the reliance on city taxpayers to fund the institution.

Barbara Floyd:

The university expanded its fiscal plans, academic offerings and research programs under Knowles, but these actions added to the financial problems. Other factors responsible for the budget plight included the loss of federal payments for World War II Veterans Programs as they closed down, a drastic decline in enrollment due to the Korean War, increased salaries for faculty, increased contributions to the state retirement system and the additional expenses of operating new buildings. As an example, the board of directors approved a budget in 1954 that would've increased tuition fees by 20 to 30%. Knowles urged city council for $200,000 more to avert the tuition increase, and council offered $25,000.

Barbara Floyd:

While they were unwilling to come up with funding necessary city council did unanimously vote to support proposed state legislation that would enable Lucas County to levy taxes to support the university in exchange for reducing tuition charge to county residents to be equal to that charge to Toledo city residents. It was projected that such an arrangement would provide 25 to $35,000 more to the university each year. Besides proposing a new funding formula, early in 1954 city council proposed that a committee be appointed to study what would be needed to establish a new medical school in the city.

Barbara Floyd:

The last time the city had a medical school was the Toledo Medical College, which was affiliated with the University of Toledo, but which closed in 1918. The American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges agreed to send experts to Toledo to study whether new school was indeed viable. In May 1954, as the medical school study continued, city council member Michael Damus suggested that the tax levy requesting county support for the university could be expanded to include $100,000 for the medical school.

Barbara Floyd:

Damus optimistically said that such a levy would relieve city council of the burden of yearly appropriations to the university, guarantee a source of funding for the university and the proposed medical college and create a first class medical center under one administration at a low cost to the taxpayer. City council's committee studying the medical school question delivered its report to the UT board of directors in July 1954. The board of directors questioned how realistic the idea of a medical school in Toledo really was. President Knowles countered that it was a popular idea with the public and was confident that the levy would be approved. One board member, Walter Eversman said, "This would be an ideal time to just submit a request to the state to make the University of Toledo part of the state's education system."

Barbara Floyd:

The medical school planning was dealt a blow when the tax levy requesting county support for the university was defeated by voters. With the defeat, Mayor Ali Salusa suggested that operating the University of Toledo as a state university would allow for an expansion of many aspects of the university. The board of directors was taken aback by the public comments of the mayor, noting that there had been no consultation between the directors and city leaders about getting the university to the state.

Barbara Floyd:

The financial situation at the end of 1954 was dire. The city was allocating $735,000 a year for the university and city council made it clear that no additional support was forthcoming. Statewide the issue was not only the University of Toledo's funding, but also funding of the other two municipal universities, Akron and Cincinnati. City council member, Jerome Janowski suggested the state could simply make the University of Toledo a branch campus of Ohio State.

Barbara Floyd:

No doubt frustrated by the budget that severely constricted the university's ability to grow, President Asa Knowles announced his resignation in 1958. To replace Knowles, the board of directors hired one of its most effective administrators, Dr. William S. Carlson. Carlson came with a great deal of experience in higher education, having served president of the University of Vermont and the University of Delaware and is chancellor of New York's Higher Education System. Dr. Carlson arrived at a time when many fundamental issues about the future of the university were coming to head all at once.

Barbara Floyd:

Enrollment projections were for ever-increasing numbers of students attending the university with limited space for all of them. The issue of a new medical school was again on the front burner, as was the state's plan to build community colleges that might include one for UT, but most important was resolving the issue of how the university moved forward, remaining a municipal institution, accepting state aid but retaining local control or ending its 75-year history and joining the state system outright.

Barbara Floyd:

In January 1959, two members of city council produced a plan to turn over the university beginning in three phases, beginning that year. The university's board of directors countered with a strongly worded resolution, urging that such a decision could not and should not be made in haste because it had many legal, economic and political implications that had to be resolved before any such action could be taken. "The citizens of Toledo now own a university that has an estimated valuation of $20 million. They have developed it and supported it at their own expense. In addition to bearing the expense of developing and maintaining this municipal institution, Toledo citizens pay the same cost to the state for support of higher education in Ohio that is paid by others living outside the city limits of Toledo who do not contribute taxes toward the support of the University of Toledo", the resolution read.

Barbara Floyd:

Governor Michael DeSell, who had then mayor of Toledo unfortunately made it clear that the state would not consider any financial assistance for at least two years. Without an option for state aid, President Carlson and the board of directors decide to go once again back to the taxpayers of Toledo. This time the request would be for a full two mills that would provide about $1.7 million annually for the university. The levy was placed on the October 6th, 1959 by primary ballot. The outcome of the levy was undoubtedly right up until the end. After a hundred polling places closed, it was behind by 700 votes and after 200 closed behind by nearly a thousand, but in the end, the levy passed by 135 votes. The university finally had some financial stability.

Barbara Floyd:

Students at the University of Toledo continued to be largely conservative in their political beliefs at the end of the 1950s, but there was evidence that that was changing. In May 1957, an uproar occurred when several dozen men decided to wear Bermuda shorts on campus, asserting their right to wear whatever they wanted. In 1960, the campus collegian endorsed Richard Nixon who had appeared in a rally in the field house over John F. Kennedy in the race for the presidency. But on November 26th, 1963, the paper issued a Special Memorial Edition after President Kennedy's assassination, urging students not to forget the ideals the president fought for.

Barbara Floyd:

President Kennedy's assassination appears to be a watershed moment that impacted UT students as it did students at other universities by inspiring more liberal political beliefs. In 1964, a rally of 7,000 in the field house for Republican candidate, Barry Goldwater, was interrupted by students who booed loudly and forced Goldwater to stop his speech several times. The event was covered heavily by the national media and Dr. Carlson was forced to write a letter of apology to the senator.

Barbara Floyd:

UT students had the opportunity to hear many interesting speakers in the early 1960s as well as musical acts who were performing new types of socially relevant music. Among those appearing in concert at the university were Kingston Trio, Odetta, The Four Freshmen, Dave Brubeck, The Chad Mitchell Trio and Peter Nero. The university's convocation program brought anthropologist, Margaret Mead and historian Arnold Toynbee to campus. For a university where most students were commuters, it did not lack in cultural programming.

Barbara Floyd:

President Carlson were to oversee the largest expansion of campus buildings in the university's history. He would also oversee several unsuccessful attempts to add new facilities, including the medical school. The medical school issue had been more or less dormant since the countywide levy defeat in 1954, but the issue was revived by President Carlson in September 1960 when he asked now-Mayor Michael Daimons to appoint a citizens' committee to again study it.

Barbara Floyd:

The assessment of a future medical school at UT completed in 1961 was blunt and pessimistic. The consultant's report said that such a school would require 10 years to build and would cost between $17 and $24 million. The university would also have to beef up its graduate and research programs. Early in 1962, the UT board of directors formally stated its approval to establish a medical school as part of the university, but only when financial support was obtained. The university said the college could be built on a 30 acres of land it had recently purchased along Secor Road as well as undeveloped land around the Glass Bowl.

Barbara Floyd:

Later in the medical school discussions, president Carlson even floated the idea of tearing down the Glass Bowl Stadium to make additional room for the College and Medical Center. In April 1962, the university got what it was seeking when the state recommended that a new medical school be built in Toledo in association with the University of Toledo with $1 million to be given to begin planning and to develop architectural designs. Most of the funding for the actual construction was expected to come from the federal government and the cost of getting a school up and running was now at $28 million.

Barbara Floyd:

In November 1962, in a bitterly fought contest, James Rhodes defeated Toledo natives son, Michael DeSell and his bid to be re-elected as governor of Ohio. Soon after the election, the state legislature created a new board at the request of the governor-elect to oversee higher education called the Ohio Board of Regents. With a new governor and new oversight, the University of Toledo's Medical Center proposal suddenly faced new hurdles. In the fall of 1963, Ohio placed state issue one on the ballot to raise $250 million for capital improvements around the state.

Barbara Floyd:

Colleges and university were expected to benefit from the levy and it was implied that some of the money would go for medical schools. $6 million was promised to the University of Toledo. The measure was approved overwhelmingly with Northwest Ohio voters leading the state in favor of the measure. With the bond levy approved thanks to Toledo voters, it appeared that all was positive for medical school at the University of Toledo. The university produced an illustrated brochure to promote the project, but questions began to surface about the school and its connection to the university, and the approval process became murkier.

Barbara Floyd:

The Board of Regents made their approval official on September 10th, 1964 in a letter to the governor. Four days later, Carlson was feeling confident that school would be approved at a special legislative session in December, but the recommendation that came from the Regents reflected a major change. The Regents recommended that the school be administered as a separate entity from the University of Toledo and have its own Board of Trustees. In January 1965, the board of Trustees of what would become the Medical College of Ohio at Toledo met for the first time with Paul Block Jr., publisher of the Toledo Blade as its chair. Block and his paper had been major proponents of a medical school in Toledo, but they had been much less supportive of it being part of the University of Toledo.

Barbara Floyd:

Some believe it was Block who convinced the governor to establish the school independent of any affiliation with the UT. The estimated price of the school was now $31 million. In January 1966, it was formally announced that the medical school would not be built on the University of Toledo campus. Despite the fact that the university's offer of land had been one of the main reasons Toledo was selected for the medical school, a new group of consultants decided that UT was too small. They recommended the school be built at Detroit in Arlington in South Toledo at the former site of the Toledo State Hospital. President Carlson expressed satisfaction that the local site had been chosen and said the university was ready to assist the new school in any way possible.

Barbara Floyd:

After years of trying to get state assistance for the University of Toledo and debating about whether the institution should become part of the state system, in the end, the approval of state status happened rather quickly and without much opposition. The medical school issue spurred on the move to state status since one of the reasons given for not building on the UT campus was because the University of Toledo was still a municipal institution and not academically ready to support a medical school. By the spring of 1965, the University of Toledo Board of Directors passed a resolution that made its case for state status to the Board of Regents. Among the reasons giving was the increasing number of people who want the college education, the limited revenue available from the city to support them and the desire to restrict tuition increases that prohibited many from attending.

Barbara Floyd:

Locally there was support for the move. Toledo taxpayers had invested millions of dollars in the university and had a right to be proud of what the dollars had approved. The last step in finalizing the agreement was the approval of Toledo residents for state status. On July 1st, 1967, the University of Toledo formally became a state university, one of the first groups to benefit from the change with the students who were paying higher tuition rates than at the state schools. As President Carlson handed over to the governor the documents that made the transfer of assets of the municipal institution official, he noted, "In a sense these represent the efforts of thousands of people, citizens of Toledo, mayors and councilmen, members of the board of directors down through the years, my predecessors in the presidency and a host of faculty members, administrators, staff members, alumni and students. We hand these over to you with pride in what all of these people have done and in full knowledge that they represent a new stronger relationship."

Barbara Floyd:

With the official ceremony to turn over the university, thus ended 83 years of local control and financial support for the University of Toledo. State status brought state money and the baby boom along with strong desire of many of that generation to qualify for Vietnam War draft deferments brought a huge influx of students to the university. The students required classroom space, laboratory space, and living space as many came from the first time from outside of the Toledo area. Because of large number of students who wanted to attend from outside of Toledo, it was clear by 1968 that more housing was needed.

Barbara Floyd:

Plans moved forward for a new sixteen-story dormitory to house 700 residents, the largest on-campus housing project in the institution's history. Married students, however, fared worse. President Carlson said he had saw no reason to construct married student housing when most married students were commuters. Carlson also moved to close down existing married student housing. Nashville, a community of 20 duplex units that had been moved to campus at the end of World War II for students attending on the GI Bill was intended at the time to be used for five years.

Barbara Floyd:

Nearly 30 years later, the housing was still the home for married students and was becoming an eyesore. The university announced in early 1971 that the housing would be demolished to make way for a parking lot and residents were informed they would have to vacate by the end of the academic year. Married students requested new married student housing be built as high rents around the university made it impossible to find some place affordable to live. The legal fights between residents of the administration dragged on, but in 1973, the university sued to evict the residents and the effort to say Nashville ended.

Barbara Floyd:

With the addition of three new state-supported universities, including the University of Akron and the University of Cincinnati in addition to UT, higher education continued to take up more and more of Ohio's budget. The constantly escalating costs of new buildings and the feeling by some that state universities were not using tax dollars efficiently led to calls to control costs.

Barbara Floyd:

In November 1968, governor Rhodes presented a bold plan for higher education that was part of his solution for the seventies program to rein in the state's budget over the long term. He proposed merging the 12 state-supported universities in 42 year community and technical schools into eight regional universities. Region four in Northwest Ohio would include UT, Bowling Green State University, the Medical College of Ohio and other two-year campuses into one university. There would be a single board of trustees for the merged institutions and vice chancellor at each campus. Rhodes plans may have been before their time. State coffers were still flush with voter approved capital improvement funds. The proposal also not surprisingly meant opposition from university administrators who wanted to preserve their independent campuses and local control. In 1970, the program was dialed back by the Board of Regents and instead of a mega regional university, the plan now called for merging only the University of Toledo and the Medical College of Ohio.

Barbara Floyd:

The proposed merger did not sit well with BGSU's President, Dr. Hollis Moore, who clearly feared what a merger between UT and MCO would mean for his university. The merger talk appears to have poisoned the relationship between President Carlson and President Moore who ended any efforts at collaboration. The merger between UT and the Medical College of Ohio would eventually happen, but not for 25 years. What became known as the Free Speech Movement began in California during the 1964,65 academic year, influenced by the Civil Rights Movement, students at the University of California at Berkeley demanded the right to free speech. After a series of protests that upended the idea of the proper role of students at a university, UC Berkeley administrators establish parameters for students on all sides of the political spectrum to have an opportunity to express their views.

Barbara Floyd:

With this new freedom of expression, students began to demand even more rights deciding university policies. The events at Berkeley influenced students on campuses across the country to use nonviolent activism to make similar gains, but as the Free Speech Movement converged with the anti-Vietnam war activism, confrontations between students, administrators, and police occasionally turn violent. Students who face the draft and feared serving in an unjust war that had already killed thousands their age, saw ending the war as a personal and a political imperative. One of the first instances of UT students peacefully exerting their rights occurred in 1967 when students from the theater department staged a sit-in outside President Carlson's office to protest the allocation of space under the theater to house computer equipment.

Barbara Floyd:

The sit-in continued for 24 hours a day over the course of several days. The situation was finally diffused when other space was to accommodate the needs of the theater department was provided. The first protests against the war in Vietnam were organized by outside groups, including the Toledo Committee for Reasonable Settlement in Vietnam, a nonpartisan group of clergy professors and professionals.

Barbara Floyd:

In February 1968, a campus organization called the Student Faculty Peace Committee took out a full page advertisement in the Collegian, calling for the United States government to stop bombing North Vietnam, to negotiate with the National Liberation Front, withdraw all foreign troops from Vietnam and declare an immediate cease fire. Students also protested against marine recruiters who were using the Student Union as recruitment site. But it was not the Vietnam War that caused the first violent protests.

Barbara Floyd:

After attempting to work with the administration to approve the quality of food that was believed to have been the source of illness for residents living in the Carter Hall dormitory, on April 4th, 1968, residents staged a food protest by throwing their food trays on the floor and food around the cafeteria. The riotous act seemed to have been egged on by local television news reporters filming the melee. Campus police arrived in riot helmets and with nightsticks. Over 20 members of the Ohio Highway Patrol also stood by. Daniel Seidman, director of Student Activities asked the law enforcement officers to please leave. The Collegian in an editorial noted the success of the demonstration.

Barbara Floyd:

At least now, the University of Toledo feels to be fully realizes that students can have legitimate complaints. It has become folly for the administration, specifically President Carlson and the Board of Trustees not to recognize the student's rights to a greater voice in this institution, not only in residence halls, but in all aspects of the university." The following month, the administration discuss adopting a national statement on student rights called the Joint Statement on Rights and Freedoms of Students. The proposed document had been written by several higher education organizations.

Barbara Floyd:

It was in response to the increasingly violent protests on campuses across the country and was hoped that the universities would adopt the statement to support students, which might help to cool tempers. The statement called for the protection, the freedom of expression, freedom of association, and freedom of inquiry. It said, "Any punishment for violating university policies must only come after a student has had the right to due process and a hearing where the charges would be presented and rebutted." The statement was approved by the UT student government, the Faculty Senate, and the Board of Trustees in 1968.

Barbara Floyd:

The increasing violence in the country and its potential impact on the university clearly concerned President Carlson. In April 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. the campus remained peaceful. Some 250 students solemnly marched to a memorial service at Jesuit Church. Classes continued, but all weekend activities were canceled in response to the tragedy. Two months later, in his commencement address of June 5th, 1968, Carlson had to quickly revise his planned remarks to make note of the assassination attempt against Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who had been shot the evening before while campaigning for present in California and who was still clinging to life. Carlson spoke about the alienation of students, about the war in Vietnam and campus unrest.

Barbara Floyd:

In part of the speech clearly inserted that the last minute Carlson stated, "But unrest is not confined to students alone. There is political unrest, faculty unrest, economic unrest and social unrest. All are intertwined. I must pause to ask a question. Who knows what combination of these and other factors leads to such a tragedy as occurred in California last night. We mourn the attempt on the life of Robert Kennedy, the American as we mourn Martin Luther King, the American and John F. Kennedy, the American. An assassin has no place in our society, yet among us there do lurk those who resort to measures that never can solve any problem, either personal or national. This Evening looking at the star example before the eyes of the world, we must mourn for our nation itself."

Barbara Floyd:

Student activism at the University of Toledo resulted in several important changes to policy that provided students with more input into administrative and academic matters. Students were accepted on to university committees and given the right to speak at Board of Trustees meetings. President Carlson was largely supportive of the request by students for more same campus operations, but his abilities to negotiate the difficult landscape and balance the needs of the university administration and the desires of activist students was challenged in 1969.

Barbara Floyd:

The organization, Students For Democratic Society was attempting to establish a chapter at the university in early May 1969. The group was known to be among the most radical of students rights organizations and many universities were working to keep the organization in check. On May 7th, about 300 students gathered behind University Hall to hear about SDS, but since the rally had not been approved through administrative channels, UT's policy prohibited the use of microphones to address the crowd. When loud music started to drown out the speakers, one of the SDS members turned on a microphone. Police requested that it should be turned off, but the students refused. Four of the SDS students were arrested and charged with disturbing the peace because they had used sound amplification at an unapproved rally.

Barbara Floyd:

President Carlson asked that all charges be dropped, but was unable to make this happen because the head of campus security had already filed them with Toledo police. On May 14th, about a hundred students gathered outside President Carlson's office door and asked to meet with him to present a series of demands from members of SDS. The president refused to meet with the entire group but did agree to meet with a small group at a time. The group's demand included abolishing ROTC on campus, ending military recruiting on campus, providing for open admissions and student control of the curriculum and granting amnesty to the four who arrested at the May 7th rally.

Barbara Floyd:

Carlson said he favored having ROTC on campus because it provided students with a career opportunity. He also would not rule out military recruitment on campus because he said it was as valid as businesses recruiting for employees. He also noted that he had been long an advocate for open admissions, so the students were taking their complaints to the wrong person. Lastly, he said that the rally of the week before had been disruptive, was in violation of university regulations, and that the fate of the students involved was no longer in the hands of the administration, was now rather a matter for the courts to decide.

Barbara Floyd:

Two days later, a small group of students, including those who had been arrested on May 7th, tried to forcibly enter the president's office. The students left after 15 minutes when campus security told them that the police and sheriff's department were on their way. The Disturbing the Peace charges against the four who organized the unapproved May 7th rally was dropped but the protesters were subsequently charged under a new Safe Schools ordinance that had recently been passed by Toledo City Council.

Barbara Floyd:

The faculty Senate took up the issue of the rally and the SDS demands at its next meeting in June and overwhelmingly approved a statement that encourage free discussion of all issues, but the Senate stated in the resolution of the matter that it "Refuses support for any person and rejects any acts that seek to disrupt university functions, interfere with lawful freedoms of expression or interfere with the rights of any person in the university community."

Barbara Floyd:

Two days later, about 150 protesters lead a boisterous but peaceful demonstration during ROTC honors ceremony on the front lawn outside University Hall. They sang songs, chanted and planted 50 white crosses at one end of the reviewing stands. Some 15 security guards were on duty and city police patrol wagons were parked across the street but did not enter the campus. Many Toledoans wrote letters to Carlson supporting his refusal to bargain with SDS. One, the mother of an Air Force veteran told the president "I want you to do everything possible to get SDS off the campus and if not possible, then hold the line so what's happening all over our great land will not happen here at TU." Another said, "I feel as many others do that as long as we back down, give in, roll over, condone and ignore these immature, outrageous actions of our college students that we can expect nothing but worse actions from them in the future."

Barbara Floyd:

UT students participated in nationally organized events in opposition to the Vietnam War, including the October 15th, 1969 moratorium that was held simultaneously on 200 college and university campuses across the country. President Carlson supported the moratorium and even gave an address at noon openly opposing the war. Carlson was one of the first university presidents in the country to express his opposition to the conflict. The day began with a memorial service at Jesuit Church were the names of 115 Toledo Servicemen who had died in the war were read.

Barbara Floyd:

One of the basic tenets of the joint statement of Rights and freedoms of students was the principal due process, but in early 1969, the university confronted just what due process meant when it applied to student athletes. UT basketball player Bob Miller, one of only four Blacks on the UT team, was a star player, thought to be on his way to a career in the NBA. In February 1969, coach Bob Nichols suspended Miller from the team, charging him with insubordination after Miller refused to attend a political science class. Black athletes raised objections to the suspension and said Miller's rights under the joint statement had been violated because he was not given due process before the suspension.

Barbara Floyd:

They also questioned if Miller was being treated differently because of his race. At a meeting of the Commission on Student Rights, President Carlson reiterated his belief that Nichols had not been influenced by racial beliefs, and the real question was whether Miller had been granted due process. The commission decided to appoint a special committee to study how the joint statement applied to student athletes. They were calls for Coach Nichols to be fired, but President Carlson both refused to fire Nichols or overrule Miller's suspension. As the issue dragged on there were rumors that there would be attempts by protesters supporting Miller to disrupt basketball games.

Barbara Floyd:

Again, many Toledoans let Carlson know how they failed on the issue. One person stated that Coach Nichols was not doing enough to recruit Black players and the coach generally only played one Black player at a time. Another letter made the comparison between the two teams at the UT Virginia Tech basketball game. She noted that most of the players on Virginia Tech's squad were Black, but she also noted that Virginia Tech fans were displaying a Confederate flag in the stands. "The grapevine has it that Mr. Nichols doesn't even care to recruit Black athletes. They're just too much trouble. I'm afraid that one can only grieve such remarks by waving that Virginia Tech spectators flag."

Barbara Floyd:

The university boasted a rich cultural life in right sixties and seventies, hosting a who's who of entertainment and intellectual leaders. Historian, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., spoke on the topic of youth and the American crisis of the time, although he called student revolts, both wrong and stupid. Other intellectuals who spoke included the comedian and activist Dick Gregory, who was nearing the end of a 40-day fast to protest the war. Author Pearl S. Buck, Arthur C. Clark, the science fiction writer who said interestingly enough in his speech that telephones in the future would become instruments to let people communicate face-to-face with anyone in the world and anti-war activist and pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock.

Barbara Floyd:

Avant-garde artists, Andy Warhol came to campus in March 1968 to talk about his work as part of the Student Union Board's Arts Festival. On the first anniversary, the assassination of Martin Luther. King Jr. the young Black activist, co-founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Georgia State Legislature, Julian Bond spoke to an overflow crowd. At the end of his talk, president Carlson announced the creation of a new scholarship fund named for Reverend King. The university also presented numerous performances by top musical entertainers of the day.

Barbara Floyd:

They included Simon and Garfunkel who performed as part of homecoming activities in November 1968 and Janice Joplin who performed in April 1969. Both of the concerts were sold out performances. The Blades Entertainment critics said Joplin's performance left both the singer and the crowd exhausted. Others who performed at the university included Iron Butterfly, John Sebastian, Kenny Rogers and the First Edition, the Fifth Dimension and Richie Havens. One group that saw their scheduled performance abruptly canceled, supposedly due to a contract dispute was a performance by The Door when vocalist Jim Morrison, who was called off after Morrison's arrest earlier in the year in Miami, Florida for indecent exposure. The university added a contract wire that required the group to pay $15,000 if Morrison committed any civil war act during the Toledo concert. A group called the Movement to Restore Decency had planned to picket in front of the field house that the concert went on, and members of Toledo City Council weighed in saying the band was a bad influence on Toledo's young people.

Barbara Floyd:

The Collegian said the Student Union Board, which had organized the concert, had little choice under the pressure, but to cancel the concert. Compared to other universities at the time, most of the anti-war activities on the University of Toledo campus were peaceful and focused on teachings and discussions on ways to end America's involvement in the Vietnam War. The Blade noted this apathy. "By national standards militant student activities at the University of Toledo in 1969 made a rather small noise and shows no signs of getting louder in 1970", the paper said in February 1970. "With few exceptions, the activism that was found among TU students in 1969 followed its traditional nature given to concerns about parking facilities, basketball tickets, and lack of student spirit", the paper continued. The paper noted that one of the reasons for the lack of militancy was likely because the students were mostly commuters.

Barbara Floyd:

But maintaining the piece met its most serious challenge in May 1970, when at Kent State University in Eastern Ohio, students gathered for a series of protests over the expansion of War of Vietnam into Cambodia. Ohio Governor Rhodes was angered by the actions of the Kent state students and called the demonstrators un-American and said they were destroying higher education of the state. After several days of demonstrations, the governor brought in the Ohio National Guard to disperse the crowds at Kent State. On Monday, May 4th, around noon, with the guard facing off against the protesters, rocks were thrown at members of the guard.

Barbara Floyd:

In response, at least 20 members of the guard suddenly fired live ammunition into the crowd of students. Some 67 rounds were fired in 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine. The killing set off a series of violence protests on campuses across the nation. As the news of the killings spread, the University of Toledo Student Senate met and requested an immediate moratorium on classes to honor the slain students and to prepare for teachings and workshops to reflect on the event. The president meeting with administrators, faculty, and students that evening agreed that a voluntary moratorium would be in effect starting at noon on Tuesday through the day on Wednesday.

Barbara Floyd:

Coincidentally, prominent Black journalist and commentator Carl T. Rowland was scheduled to speak on campus on May 5th. His speech titled Revolution in the USA went on a schedule but was moved outside to the the front lawn of the Student Union where it drew a crowd of 3000. President Carlson and several faculty and students also spoke. Rowland made the case of the killings at Kent State were an indication of violence beginning violence, just as the bombing of North Vietnam and the spread of war into Cambodia would also bring more violence. "There is no logic and no morality in telling one group of Americans that they have the right to burn and kill in Indonesia for what they believe, but to tell others that if they throw stones for what they believe, they risk on-the-spot execution by the National Guard", Rowland added.

Barbara Floyd:

That afternoon the UT Faculty Senate passed a strong resolution condemning the deaths of the students at Kent State and America's continued fighting in Vietnam. "The inability of young people who are most directly concerned with the fighting of an unpopular war to effectively alter the policies of the nation have led to frustration and bitterness on their part. Instead, they have been faced with a broadening of the conflict in the name of peace. Cynicism and despair now have as the product of this latest evidence of their helplessness. Violence, and killing at home have become the ultimate phase of this struggle", the resolution said. It ended with a call for peace.

Barbara Floyd:

We call on this community and in all university communities to eschew violence. We pledge the continued maintenance of an open and free community along the tradition of American universities. Some students met with Carlson and presented a series of the demands for removing a reserve armed unit from campus, removing all ammunition from the ROTC building and requesting the campus security not carry guns in the daytime. The president agreed to the terms of the students. Some 1500 participated in the candlelight vigil on Wednesday, and a massive meeting was held in the field house on Thursday.

Barbara Floyd:

Students Organized for Peace prepared a list of resolutions passed by students and faculty, which included giving 18-year olds the right to vote, defunding the war effort and asking for federal subsidies to help pay for college education. They also voted to prohibit the National Guard on campus. An all day session of dialogue between students and faculty was held on Friday and on Saturday, the Student faculty Peace Committee conducted a march through Downtown Toledo. Even mothers of students became involved when a small group stood vigil at four crosses erected on the front lawn of the university in honor of the slain students. The campus remained peaceful in the moratorium continued the next week, but was maintained on a voluntary basis.

Barbara Floyd:

Other campuses in Ohio turned violent. The Ohio State University and Miami University were shut down after clashes between students and police. President Carlson sent a memo to all faculty expressing his thanks for their "forbearance and cooperation, and helping to keep the cool the last several days. The results have been good in contrast with experience on many other campuses." The Toledo Blade congratulated the administration for preserving the peace and also express support for the students for their "feelings about this sorry war and all it has brought to this land, but they have done so without the burning rioting and other violence resorted to elsewhere that this vigorous dissent was registered peacefully is a credit to all concerned."

Barbara Floyd:

The reaction of the UT campus and the administration to the shooting at Kent State contrasted sharply to those a week later when two Black students were shot to death on the campus of Jackson State College in Mississippi. There was no moratorium on classes, no campus wide memorial service, and no public declaration of sorrow from the administration.

Barbara Floyd:

On Monday, May 18th, a group of Black students began barricading University Hall around six A.M. and refused to let students and into the building. The Black students were angered by what they saw as a lack of respect for the students killed in Mississippi. Representatives of the Black Student Union said the contrast and reaction to the deaths at Kent State and those at Jackson State "indicates to us that the university administration feels that only white deaths are to be mourned while Black deaths are insignificant and go ignored. Therefore, it would appear to us that the value of Black lives in America are not equated with those of whites." That morning, representatives of the organization met with President Carlson in his office and presented a series of demands before they would end the barricade and allow classes to resume. Carlson later admitted that he lost his temper during the meeting and he turned over deliberations to other administrators.

Barbara Floyd:

Among the demands of the students were $200,000 for Black Studies program, hire a full-time coordinator of Black studies, prioritizing the hiring of Black professors, a Black student enrollment commensurate with the population of Blacks in the city of Toledo and a minimum of three Black graduate students in every department. Tensions began building outside of University Hall between white and Black students. After some negotiation, President Carlson agreed to set aside funding for most of the demands, although at lesser amounts that the Black Student Union had requested. The protest ended at 11 A.M. when results of the discussions were made public. In a page one editorial, the Collegian called the outcome of the discussions a reasonable response to legitimate requests. A memorial service was held for the Jackson State students later that week. In his remarks, President Carlson urged the students to work together with the administration for a peaceful end to violence on university campuses.

Barbara Floyd:

"Let us mourn our loss, let bind up our wounds and let us search together for new and humane ways in which men can resolve their differences in harmony and goodwill rather than in bitterness and anger", he said. While President Carlson may have had the support of many on campus force meeting with the Black Student Union and agreeing to some of their demands, the same was not true for many in the Toledo community. A WSPD editorial denounced the agreement as prohibitively high price for peace and was especially critical of Carlson's willingness to negotiate with the students while the barricade continued. "A regrettable dire has been cast", the editorial concluded.

Barbara Floyd:

Many citizens bombarded the president's office with letters. Only a few were supportive of Carlson's actions. Many were outright racist. Most echoed the sentiments of one alum who said, "You are kidding yourself and letting down the community by giving into minority demands that are a result of brute force, boycotts and unruly mobs that choose to close the school at their whims."

Barbara Floyd:

The tragedies of campus unrest in 1970 led to the appointment of a statewide Ohio Select Committee to study campus disturbances. Report to the committee, which was issued in the fall, blamed the unrest not on foreign wars or societal problems, but rather on the situations on campuses themselves and called on the academic communities on those campuses to solve their own problems. The committee said the politicization of universities was inappropriate and also said any involvement with groups trying to disrupt universities should be avoided. The committee's work looked far beyond disruption and into issues like how faculty received tenure, how misconduct by students was reported and dealt with, and called for an adoption of a code of conduct for both students and faculty, more centralized power over university operations by board of trustees and immediate efforts to eliminate drug use on campus.

Barbara Floyd:

After several lengthy criminal investigations into the Kent state shootings, no criminal charges were successfully attained against the National Guard members. A civil case filed by the families of the slain and injured was settled for $675,000. In Mississippi the killings at Jackson State resulted in no arrests, although an investigation called the shootings Unreasonable and an overreaction. The decade of 1960s ended with a much changed University of Toledo. Many credited the leadership of President William S. Carlson for both the positive changes and a lack of violent protests that had been experienced at many other universities. UT was no longer a municipal university supported by Toledo taxpayers, but was now a member of the state's higher education system.

Barbara Floyd:

With this move brought necessary funding, both for operating expenses and for many capital improvements, but it also fundamentally changed the relationship between the city and the university. The university was no longer Toledo's University, but was instead a University of the city and operated and funded by the state. State status led to a major growth in the enrollment, which allowed the university to expand its curricular offerings and faculty ranks, but this growth also met the end for the sometimes quaint and close-knit feelings of the campus that led to it sometimes being called Bancroft High.

Barbara Floyd:

More and more students came from outside Toledo, which brought diversity to the student body, but this served to further cut the tie between the university and the city as students from outside Toledo were less likely to stay in the city once they received their education. Fortunately, as America's involvement in the Vietnam War began to wind down, and most importantly, the drought that threatened the lives of many young people, student activism on college campuses changed. Students began to work within the administrative systems to enact change through more participation in governance and the structure of the university.

Barbara Floyd:

Today, we can still see the impact of the 1960s on the University of Toledo. It is much larger, better funded, more academically advanced, more diverse, more politically attuned, and a more mature university. These changes all began in the decade of the 1960s, and they happened not just at the University of Toledo, but on campuses across the nation. Today we often look back on the decade of the 1960s with an air of nostalgia, but what happened on college campuses is more than long hair, rock music, student protests, marches, and drugs. The events of the decade was represented profound historical movements that fundamentally changed higher education in ways that are still evident today.

Barbara Floyd:

Thank you very much.

Emily Rinaman - "'Seneca Strolls' - A Publication of the Tiffin-Seneca Public Library" (October 16, 2023)

Emily Rinaman, Technical Services Manager at the Tiffin-Seneca Public Library, discusses the Seneca Strolls blog she created and writes for the T-SPL. Rinaman's blog post, "Let's Band Together," about the history of community bands in Tiffin, Ohio, was the winner of the CAC's Local History Publication Award in the Independent Division's Article Category for the year 2022.

PDF Transcript of "'Seneca Strolls' - A Publication of the Tiffin-Seneca Public Library"

Emily Rinaman:

Part of the reason I love working in a library is because I get to hide back in the technical services room where I digitize historical items and catalog the new books coming in. Unlike writing, speaking in front of a crowd, like this small one today, it might be small, but it's still big enough for me, it's not one of my fortes. So I confess that I will be reading today's presentation from my written transcript so I don't stumble over my words. I hope you all enjoy all the cool photos I have on my PowerPoint presentation, because they will be much more interesting to look at rather than staring at me for the next 45 minutes.

I believe in serendipity. I believe in signs. I believe we all have a purpose, and you know you're making the right decision when you feel it in your heart. One afternoon this past spring, I was sitting at my computer at work researching for one of the Seneca Strolls blog articles. I hadn't devoted any attention to this blog in a while, and I knew I needed to stop pushing it aside and work on it. We all know how that feels, right? Sometimes I get in my own head, and on this particular day, I was second-guessing myself, "Does anyone read these blogs? Am I doing this research for nothing? Is it taking up too much of my time? Should I just abandon the whole project?"

So I decided to take a break from my research and check my email, and that was when I had received the email from the BGSU Center for Archival Collections that I had won this award. The timing of this announcement could not have been any more prophetic. It was a confirmation that my doubts were all for nothing.

Okay. Well, I want to make it clear that I feel very blessed to be in a society, a career field and a position in my field where we are all actively making reparations towards the injustices that certain cultures and groups of individuals have experienced in our nation's history. It doesn't mean I always condone what's happened in the past and how these people have been treated. On the flip side, I believe addressing all of history can remind us how far we've come and motivate us to keep moving in the right direction.

For generations back to 1833, my paternal family has kept deep roots in Seneca County, Ohio, and I, therefore, have always felt compelled to find a way to keep Seneca County's history alive in their honor. This stained-glass window is from that church that myself, my father, who's here today, my paternal grandfather and many of his family members grew up in, the parish that our original ancestors from Bavaria Germany founded just a few years after immigrating. The window graces visitors to my home when they walk through our front door. My husband and I recently built this house just a few rule blocks over from where the church once stood for over 100 years before being demolished just within the last five to 10 years.

I have always loved books, and as a little girl, often imagined myself becoming a school librarian, in between my dreams of being a figure skater, as I watched Scott Hamilton and others skate on TV. Figure skaters like Tara Lipinski, Kristi Yamaguchi, Nancy Kerrigan and Surya Bonaly were my celebrity idols growing up. My parents always supported my dreams and I owe a large part of the reason I'm standing here today because of them. They've always known how determined I am, and my dad, a 1976 BGSU graduate, even signed me up for figure skating lessons here at BGSU back in the '90s when I was around 11 or 12 years old.

I was surrounded by girls half my age who were probably a little more serious about competitive figure skating than I was. I am pretty sure my baby photo album is still packed up somewhere after our move last year, so here is a collage of each of my three children's first time ice skating. Each of them were around four to five years old when they skated for the first time. They all look like me too, so just imagine that same face, but with 1990s attire, and you'll get the picture of myself in the Slater Family Ice Arena.

Luckily, it was around this time I had figured out what I truly wanted to be, a writer. Around the same time, at Christmas, my paternal aunt and uncle presented me, my brother and each of my cousins with a three-ring binder full of information about my ancestors and an extensive family tree. This was back in the early days of the internet, therefore, they had to make in-person visits, write letters, make phone calls, et cetera, to gain all this information from various libraries. They put a lot of time and effort into this project, and I realized how much love was contained in that binder.

I learned that I have branches in my family tree on both my paternal and maternal sides that have roots in Seneca County for several generations. It was in that moment my passion for learning about the past bloomed. I'll always be grateful that I was able to tell my aunt how much that gesture meant to me and how much it guided me on my life path before she passed away after a decade-plus long battle with metastatic breast cancer in May of 2022.

I graduated from Heidelberg University in 2006 with a major in English, emphasis in writing, and minors in Spanish and Latin American studies. My first job out of college was a reporter and photographer for the Focus in Fostoria. I didn't enjoy it as much as I thought I would, and I shifted to a part-time position as the serial supervisor at Beeghly Library at Heidelberg College for five years. It was there that I decided to pursue a career in the library field. When we went through a remodel, new carpet, and had to temporarily migrate to the building next door over the summer, I was given the task of digitizing the old college catalogs. Being an alum myself, I found it fascinating to see how the university evolved over the years.

I then worked in various roles in both the advertising and editorial departments of the Advertiser-Tribune in Tiffin while working on my master's in library and information science degree, which I received online through the University of South Carolina in December of 2015. By that time, I had been volunteering at the Tiffin-Seneca Public Library since 2014, digitizing local history items for the former technical services manager, JoAnne Schiefer.

When the outreach department manager position at T-SPL became open and I was hired to take that role, I was able to continue to digitize once a week while serving in the outreach position. I took over as technical services librarian in June of 2018, and then eventually became the technical services manager in May of 2022 when JoAnne retired, and as you recall, that's the same month my aunt passed away.

Okay, so my idea for the Seneca Strolls blog was twofold. It was first and foremost an avenue to promote the Seneca County Digital Library, which I will refer to as the SCDL for the remainder of this presentation, and to get people to peruse the many items we've digitized. The SCDL started in the fall of 2009 through an LSTA grant with the help of NORWELD, which is the Northwest Ohio Regional Library District Consortium, and is located here in Bowling Green. The grant allowed 11 other libraries, in addition to T-SPL to digitize items. It covered the cost of a flatbed scanner and membership to the Ohio Historical Connection, which is required to be able to upload your digitized items to the Ohio Memory Project. The Ohio Memory Project is a piece of the Ohio Digital Network, which in turn, is part of the Digital Public Library of America.

One of the first collections digitized with the grant funds were the high school yearbooks. We now have over 3000 items digitized onto the SCDL, including court records, such as naturalization records, commissioners' journals from the 1800s, League of Women Voters meeting minutes, items loaned from Tiffin University, postcards, letters written to and from Louisa, suffragist Louisa K. Fast, club programs, various items pertaining to the Junior Home Orphanage, plus 100s of photographs and oral histories. Our most recent ongoing project after receiving the brand new scanner is digitizing the original birth and death records for the small villages and townships in Seneca County.

When I can't find appropriate photos for my blog articles, I use photos from the Ohio Memory Project from other institutions with permission. So this here is an example of that. This shows the interconnectedness of libraries, museums and other cultural heritage centers. For example, the technical services staff at T-SPL and library staff here at BGSU are part of two groups, the Northwest Ohio Cultural Heritage Group and the OhioDIG Group. Both are made up of different types of institutions that all have active roles in preserving cultural heritage and the physical items that illustrate that heritage.

While these groups include public libraries and academic libraries, there are also members from museums, archives and special libraries within places like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, for example. Through our collaborations, we share a multitude of ideas. So the next time you visit a museum, you know that training libraries probably had a hand in gathering the information for the displays, and likewise, when you visit a library, don't discount the idea that museum staff may have helped the librarians put up a historical display.

We, ourselves, partner with the Seneca County Museum for our display cases and did a joint military-themed display over the summer. Part of that display was showcasing Ohio's Underground Railroad trails, and we highlighted the ones that went through Seneca County. Therefore, I have to give partial credit to the Sandusky Public Library and the Hayes Presidential Center in Fremont because my idea for the Seneca Strolls blog was born from a meeting of the Northwest Ohio Cultural Heritage Group held in the summer of 2009 when both of these institutions shared they had active blogs to bring awareness to their histories and collections. That's a closeup of the Underground Railroad trails through Seneca County up to Sandusky that we had in the display case.

My second reason for taking on a blog project was because I become passionate to get people as excited about history as I am, especially local history. We are currently in an era where people are energized to revitalize downtowns, making them modern, while simultaneously maintaining some aspects of the historical foundations of the buildings and their pasts, including Tiffin, and Bowling Green has a nice downtown as well.

So the main intention of the blog is to show how the residents and culture of Tiffin and Seneca County fit into a wider hole. It shows how Tiffin and Seneca County fit into bigger trends. Because Tiffin is a small city and Seneca County is a very rural area, its residents can sometimes feel behind the times. My blog articles try to dispel that myth and try to express that we actively create our own histories.

So once I came back to T-SPL and presented my idea for a blog to JoAnne and our director, Matt Ross, and they gave me the go ahead to start creating it, we needed to come up with a name. We put out a stat poll with a few ideas that JoAnne and I came up with together, and our staff voted for Seneca Strolls. JoAnne selected the blog's signature photograph you see here from the SCDL. It's a photograph of a group of teenage girls taking a walk on the Junior Home Orphanage's grounds in the 1940s shortly before it closed.

Matt had suggested that I have a bunch of articles written in advance, since our marketing and communications manager can schedule them. I quickly set to work researching ideas on a multitude of topics. On a side note, this proved to be good hindsight because the pandemic hit right when we were debuting the blog. Our staff then shifted to a temporary hiatus followed by a modified work-from-home situation before returning in varying staggered capacities in the building. The blog was something I was able to work on from home.

I used the Chase calendar of events to come up with a lot of ideas, but I also included historical topics of wide interest that I thought could be researched well or that I knew we had plenty of information about on the SCDL. Some of these topics include the evolution of theater, pharmacies, handwriting, timekeeping, morning practices, meals, exercise and sports, and much more. While my focus tends to be a 100-year time span, give or take between the 1850s through the 1960s or '70s, sorry, Dad, but that's considered history to me at this point, I sometimes try to be cognizant of the distant past. We, unfortunately, only have a small collection of documents on underrepresented groups at the moment, and at some point I'd like to do a diversity audit on the SCDL to try to improve this disparity.

For my inaugural article in January of 2020, I wanted to do something that would entice a lot of people, since anyone with marketing experience knows it takes several attempts to get people to catch on to a new idea. So with the Super Bowl approaching, I wanted to do an article on pizza, which actually has a very interesting recent history in the U.S. directly tied to World War II. I was successful in setting up an in-person interview with John Reino, the current owner of a multi-generation, family-owned and authentic Italian pizza restaurant in Tiffin, Reino's.

I ended up finding his grandfather's naturalization record on the SCDL. This gives me goosebumps even today, right now, and he was extremely humbled by the fact that we had digitized it. This was one of the photos that I used in that particular blog article and is shown here. So Reino here is spelled R-E-N-O. So I pointed out at the top, Reino's today, they spell it R-E-I-N-O. So just an example of certain disparities when they came here and had a form filled out, but he signed it Giovanni Reino, which is really neat, but just John's reaction to seeing his grandpa's naturalization record, that's what really made it feel important for me to be doing this.

Other people I have interviewed in the community include a local certified auctioneer, a local ham radio expert and the current owner of Jolly's Restaurant, another longstanding Tiffin staple known for its homemade root beer, and there's some jugs that you used to be able to take to Jolly's and get them refilled, I guess. So I think that was before my time, but I interviewed him on my article for home delivery trucks and how they've evolved into the current food truck craze.

Okay, shortly after the blog began, T-SPL's previous program manager came to me asking if I'd be willing to coincide my February 2021 blog article with an event the library was hosting called Things We Keep, since this topic, in and of itself, involves history. After perusing the SCDL to determine which angle I felt I could present well, I decided to focus on cornerstones, which is the idea of a community or organization keeping a select array of items within a newly erected buildings foundation. After this collaboration proved fruitful, our marketing and communications manager and I tried to coordinate the library's biannual community read themes with that month's blog article.

In April 2022, I did an article about apples to pair with the book, At the Edge of the Orchard, by Tracy Chevalier, or maybe ... I'm not good at French. Spanish in my language, not French. Last October, I wrote about the evolution of the pharmaceutical industry to match the book, Ghosts of Eden Park, by Abbott Kahler. This past April I focused on maps, which was a key component in the novel, The Apothecary, by Sarah Penner, and for this month's blog, I've done a piece on poems to go with Maggie Smith who visited us just on October 10th for her book called Goldenrod, and another book, her memoir, You Could Make This a Beautiful Place.

Looking forward to next spring, we'll be reading The Paris Daughter by Kristen Harmel, and that has ... Art is a major component in the main character's life. Events will be in late April and early May, so I'll be writing a piece on comics and billboards for April, and garden decorations in May.

When I took over as manager of the Technical Services Department, I started having our Throwback Thursday posts on Facebook centered around each month's blog theme. Our Throwback Thursday posts are pretty popular, and so I saw this as a way to get the word out about the Seneca Strolls blog. The two staff members in my department and I have a rotating schedule for these posts. Because our collaboration on the former Junior Home in Tiffin is so massive, one devotes the first Thursday's post to grabbing tidbits from those items that relate to the blog article theme. The second Thursday is devoted to our school yearbooks and the fourth Thursday features T-SPL's history. The third Thursday's post is always a link to that month's blog article, which is released onto the Seneca Strolls blog page that day.

Our marketing and communications manager always takes a sentence or two from the articles as an attention grabber, and chooses one of the photos, as I normally include two to four photos per blog article. The Facebook post for the band's article, for which I'm receiving this award, reads, like most communities, Tiffin has a fantastic musical history. The latest Seneca Strolls blog talks about the different kinds of bands that have called Tiffin home over the years, including Steine's Band pictured here. Now that's not ... That's the Junior Home Marching Band, which was another picture I had in the blog.

And then she quoted my blog article. 1000s of German immigrants called Tiffin home, and one of the traditions they brought with them to America was their love of music and a strong kinship of playing music together. The American groups served as bridges between old and new worlds preserving ethnic traditions while shaping the culture. Steine's Band was perhaps the last of its kind and performed well into the 1940s. It even had its own theme song, Roll Out the Barrel, a Czech polka composed in 1927.

In the next several slides, I'd like to share the impact that the Seneca Strolls blog has made using direct quotes from comments posted on the blog itself and on our Throwback Thursday posts on Facebook. Before I do that, I just want to pause, because, just recently, my husband, he works at a factory in Tiffin, and we went to a Mud Hens game for his work, and the granddaughter of Steine, who started Steine's Band was there because she works in the factory, and so my husband was alongside. He's like, "Oh, here, here's the granddaughter of the ... that article you wrote on the bands." Well, we got talking to her, and she said that she has some of those instruments in her garage or something. So that's just an example of a way that you connect with people through stuff like this, and it just made me laugh that my husband was all excited about, "Hey, I'm connecting you with her." So I'm like, "Hmm, oral history in my future?"

Okay, back on track. Preserving and sharing history is a way to connect to our ancestors. One of my favorite blog articles I've done so far is the one I did on card playing, where I used a photo of men in my paternal grandmother's hometown of New Riegel in the southwest corner of Seneca County playing the regional card game of Euchre, and I just want to know, by a show of hands, how many people know how to play Euchre? Okay, that's pretty good. Some people are like, "Euchre? What's Euchre?" I'm like, "Oh, my God."

Okay. Anyway, on a side note ... Oh, wait, and then I've talked about, if you've never heard of Euchre and don't know how to play, I highly encourage you to find someone who does and have them teach you. This card game continues to stay very well alive to this day, because it keeps getting passed down. In the Midwest, especially this area of Ohio, it's almost a rite of passage when you learn how to play.

All right, anyway, I'll start off the quotes section of my presentation with a response to the article on bands, for which I won this award. So that's at the top there. "As an old Akron High School band member, I really enjoyed this article. My Tiffin ancestors from Germany originally lived in Fremont. I would love to be able to find out if they had a band also." Then, the bottom one is just on my article of rationing, and earlier I pointed out that photo, the rationing card. "Thanks for putting the COVID shortages into a historical perspective, especially a local historical perspective. I remember my parents talking about World War II rationing, and I have some old coupon books in a cedar chest. My mother thought that history was worth preserving. Great overview of the groups and organizations who stepped up to help the needy." Bravo, Emily, is how she ended it, but I didn't [inaudible 00:22:09].

Okay. Preserving and sharing history is a way to connect to our own pasts and carry that onto the next generations. In response to my articles on parades in September 2021, quote, "Too bad the Heritage Festival was canceled this year. I fully enjoyed being in the parade and scrubbing on my washboard to marching music with Mary Lewis and companions." And then, article on timekeeping. "Crazy to be reading this today. My six and seven-year-old grandchildren and I were just talking about how we used to have to look up a book in the library, a.k.a. the card catalog. I loved doing it and things that are obsolete or almost obsolete, such as wall clocks, phone books and landlines. We had that conversation, actually, in a Tiffin library." So there's Steine's Band, what I was talking about earlier.

Okay, both of these quotes are in response to a Throwback Thursday post related to my article on basketball in December 2022. "Love this. That's my daughter, Angie, back in high school." So this was one of the yearbook posts. "That was a great season, great teammates and coaches. She now has a son, Logan, playing his senior year at Columbian High School. Things come full circle." And then another quote, "It was a weird type of basketball, though. The kind I played in high school was only half court and three dribbles was the limit, and six players. Girls couldn't be expected to play full court, might damage the childbearing equipment or something."

Okay, digitizing items on the SCDL helps us receive facts from residents in the area who know historical facts about Tiffin and the surrounding area that we might not. The following is a response to my article on auctioning. "The linked article by Emily Rinaman mentions a second auction at the Daughters of the American Revolution home. Confusing the two organizations is a common mistake. The retirement home was actually for members of the Daughters of America, the auxiliary of the Jr. O.U.A.M," which is referring to the Junior Home that I talked about earlier.

And then, this one here is one of our favorites. So this was an article I did on kindergarten, because kindergarten didn't always used to be required. "That photo is a picture of my mom. She passed away in September 2009. Seeing this photo is wonderful." So that picture garnered a lot of talk. She was a teacher, I guess, and some of her students remembered her, and so it was just a way to remember her, and then we got her name. So now we can put her name on her picture on the SCDL.

Okay, digitizing items on the SCDL allows others to share our history too. So, recently, so this picture doesn't actually go with the quote. I was just trying to put pictures for you to look at while I talk, but this here, the Tiffin-Seneca Heritage Festival Facebook page used our photos, and they credited us when they shared them, and they say, "Unbelievably, the Tiffin-Seneca Heritage Festival is just around the corner. Thanks to the Tiffin-Seneca Public Library's digital collection, we are going to share some of our favorite festival memories from years past, starting with 1979, the first year of the Heritage Festival, showing a huge crowd on the North Washington Street Bridge looking towards downtown Tiffin."

And then, I have another direct link to a specific item on the SCDL, has been placed on frostvillageinn.com in its neighborhood history section. Frost Village is a section of Tiffin by the Sandusky River with several stately old homes and a business that has taken over the building once owned by the Tiffin Women's Club. A link to our digitized version of the history of that particular building that we digitized is available on that website.

We have many other general referrals as well. The Tiffin Columbian Athletics page has us listed under their city archive section, so we get a handful of referrals from there each month. Tiffin University's Pfeiffer Library has a link to the SCDL in their research databases section. A website dedicated to the Lucas family tree of Northwest, Ohio, credits the SCDL, as well as the Seneca County Genealogical Society and the Fostoria Lineage Research Society, and according to our Google Analytics stats, because of our presence on the Ohio Memory Project, patrons at many other libraries in Ohio have found their way to our digitized items through their home library websites.