Archival Encounters Podcast

Where archives come alive, and past voices meet our present moment.

The Archival Encounters podcast series highlights items from the CAC’s collections, particularly oral history interviews, to bring voices from the past into conversation with the present. In each episode, we encounter unique stories and figures documented within our multifaceted collections, and invite a BGSU scholar or community expert to contextualize their legacies and illuminate their relevance to the world today.

(Cover art by Ben Boutwell, Media Production and Studies major, BGSU School of Media and Communications)

Episode 2: Northwest Ohioans in World War II: The History 303 Veteran Oral Histories Collection

Our second installment of Archival Encounters is a three-part episode on World War II, in which we’re chronicling the American experience of the war through the oral histories of six veterans from Northwest Ohio, including John Andryc of Rossford, John Damman of Napoleon, Gordon Domeck of Wauseon, Allie Schrader of Belle Center, Pete Simon of Custar, and Jim Spencer of Bowling Green. These oral histories are part of the CAC’s larger collection of over one hundred World War II veteran oral histories that were collected by BGSU students in the early 2000s for History 303, a course on World War II taught at the time by Assistant Professor Walter Grunden and doctoral candidate Kathren Brown in the BGSU Department of History.

Our second installment of Archival Encounters is a three-part episode on World War II, in which we’re chronicling the American experience of the war through the oral histories of six veterans from Northwest Ohio, including John Andryc of Rossford, John Damman of Napoleon, Gordon Domeck of Wauseon, Allie Schrader of Belle Center, Pete Simon of Custar, and Jim Spencer of Bowling Green. These oral histories are part of the CAC’s larger collection of over one hundred World War II veteran oral histories that were collected by BGSU students in the early 2000s for History 303, a course on World War II taught at the time by Assistant Professor Walter Grunden and doctoral candidate Kathren Brown in the BGSU Department of History.

In this three-part episode, Dr. Grunden, now a full Professor in the BGSU Department of History, serves as our expert historical guide as we follow our six Northwest Ohio veterans’ firsthand accounts of their World War II service. Along the way, we’ll situate our veterans’ narratives within the larger context of the war, and we’ll learn how our veterans’ wartime contributions are both unique and also reflective of the experiences of millions of ordinary Americans who served in the global fight against fascism that would define the twentieth century.

This is Part 1 of a three-part episode; stay tuned for Parts 2 and 3!

Nick Pavlik:

From the Center for Archival Collections at Bowling Green State University libraries, this is Archival Encounters, where archives come alive and past voices meet our present moment.

The Center for Archival Collections, or the CAC, collects, preserves, and provides public access to unique historical records documenting BGSU, the Northwest Ohio region, the Great Lakes, and National Student Affairs, as well as an extensive rare book collection.

I'm CAC archivist Nick Pavlik. And in this podcast series, we're sharing some of the many important stories that our archival collections have to tell. We're especially focusing on oral histories, recorded personal remembrances of historical and biographical events as told by those who lived them, providing living eyewitness accounts you likely won't find in the history books.

September 1st, 1939.

Speaker 2:

These are the days' main events. Germany has invaded Poland and has bombed many times.

Adolph Hitler:

[speaking German 00:02:09].

Speaker 3:

I, therefore, resolve to speak to Poland in the same language in which Poland has addressed us for such a long time.

Speaker 4:

We shall fight this war for Poland. For the sanctity of our home. For their right to maintain our faith and our tradition.

Adolph Hitler:

[speaking German 00:02:27].

Speaker 3

From now on, bomb will be met by bomb.

Speaker 5:

This is London. You will now hear a statement by the Prime Minister.

Neville Chamberlain:

Consequently, this country is at war with Germany.

Speaker 6:

This morning, the United States was awakened by the voice of Prime Minister Chamberlain of England, declaring that a state of war existed between that country and Germany.

Speaker 2:

General mobilization had been ordered in Britain and France.

Speaker 6:

So swiftly followed development after development in this history-making day. And now ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt:

When peace has been broken anywhere, the peace of all countries everywhere is in danger.

Nick Pavlik:

Under Adolph Hitler, Nazi Germany invades Poland, setting into motion the catastrophic events of World War II. Over six long and brutal years, the Allied powers consisting principally of the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and eventually the United States would engage the Axis powers consisting principally of Nazi Germany, the kingdom of Italy, and the empire of Japan in a series of relentless and bloody conflicts that would truly engulf nearly the entire world.

Before the conclusion of the war in Europe and the Pacific marked by the surrender of Germany in May 1945 and the surrender of Japan in September 1945, the war would result in the deaths of nearly 80 million military personnel and civilians throughout the world, including the deaths of the nearly six million Jews who were systematically murdered by the Nazis in the Holocaust, and would introduce the world to the horror of nuclear weapons. The aftermath of the war would bring about the irrevocable transformation of the political world order.

Over a half-century after the war, at Bowling Green State University's Department of History, Dr. Walter Grunden and Dr. Kathren Brown began teaching History 303, a course on World War II in which students were encouraged to undertake the special optional assignment of conducting an oral history interview with a World War II veteran. For those students who chose to take on the assignment, the veteran they interviewed was often a family member, such as a grandparent or a great uncle or aunt, or it was a veteran with whom they had been connected through one of the local veterans organizations here in Northwest Ohio.

By 2004, History 303 students had conducted over a hundred oral histories with veterans of the war and the collection of History 303 oral histories was donated to the CAC so it could be preserved and made accessible to the public. Today, thanks to a grant awarded to the CAC in 2018 by the Ohio History Connection’s Ohio History Fund, the entirety of the History 303 veteran oral history collection has been digitized and made freely available online.

In this three-part episode, we'll be recounting several of the major events of World War II focusing on the role of the United States with History 303 instructor Dr. Walter Grunden as our guide. Along the way, we'll hear from six veterans from Northwest Ohio who were interviewed by BGSU students for History 303 in the early 2000s. And we'll learn how their experiences of the war are both unique and also reflective of the experiences of millions of ordinary Americans who served in the global fight against fascism. And just a note to listeners. This episode features some explicit language and graphic descriptions of military combat.

Let's get introduced to our veterans.

Jason Gray:

Today is December 12th. It is around noon right now of the year 2000. My name is Jason Antony Gray. I'm a senior at BGSU, and I'm here with John Andryc at his house in Rossford, Ohio just south of Toledo.

Derek Damman:

This is Derek Damman for History 303, Professor Walter Grunden, fall semester, 2003. I'm interviewing John Damman retired technician sergeant, fourth grade US Army, December 9th, 2003.

Josh Oyer:

This is Josh Oyer, History 303, Dr. Kathryn Brown, summer 2002. I am interviewing Gordon Domeck. He was a corporal in the United States Army, Company A, 33rd infantry of the 84th Infantry Division.

Scott Vermillion:

Scott Vermillion, History 303, Dr. Kathryn Brown, fall 2001. Interview with Allie Schrader, retired from the United States Navy, was a seaman first class in resting gear. November 29th, 2001.

Alexis Osborn:

Alexis Osborn, History 303, Professor Walter Grunden, fall 2003. Interview with Pete Simon, retired T-5 corporal. December 5th, 2003.

Matt Gamber:

Matt Gamber, History 303, History of World War II, Dr. Kathryn Brown, spring of 2001. The following is an interview with retired major Jim Spencer on April 2nd, 2001. Spencer served World War II in the Southwest Pacific with the 148th Infantry of the National Guard from 1941 until 1945.

Walter Grunden:

I mean that class, World War II, is a very popular class and it always fills.

Nick Pavlik:

And that's Dr. Walter Grunden.

Walter Grunden:

I teach in the Department of History here at Bowling Green State University. My major area of expertise, if you will, is modern Japanese history, but I also study modern China, East Asia, more broadly. My research specialization is in advanced weaponry of World War II and the Cold War era. And particularly what the Japanese were working on in World War II in terms of advanced weaponry.

Nick Pavlik:

With the History 303 course, Dr. Grunden wanted to provide students with an enriched understanding of World War II that could really only be provided by someone who was there.

Walter Grunden:

My objective in getting the students out to do these interviews was to get as close to the firsthand experience as they could. It's one thing you read about World War II in a textbook. It's another thing you get some supposed expert like myself standing in front of a class and talking about the war and so forth. But none of us were there. None of us had that experience. I wanted them to have the opportunity to sit down across from someone who was actually there, experienced it, or whatever their experience was, right?

Part of the value of this is just getting the stories of the every day more common soldier, sailor, airman, and even some of the women who may have been in a wax or the waves and to capture their stories from the ground up. This is always the danger of history. Of course, the victors write the history. And then the high command, there's an official narrative that gets created about the war. And we learned that's the official story that we learned K through 12 or in college, but there was so much more to the story and you won't get to that unless you talk to these folks who are literally in the foxholes, literally on the ships, literally on the front lines. And some of the stories they have to tell as you know, are incredible. I mean, it's just really fascinating.

Nick Pavlik:

Do you recall how the students describe their experiences of having done the oral histories and whether their understanding of the war changed as a result of the opportunity to do these interviews?

Walter Grunden:

I think it did change their perspective on the war because again, I think it helped them to personalize the war instead of it just being from a dry history textbook or from one of my lectures, they actually sat down with somebody who was there and they could see the emotion of the memory and the thoughts. They would tell them things that is not in the textbook, it's not in my lecture, and they get that one-on-one experience with a veteran. So I think it personalized the war for them and it made it more real.

Nick Pavlik:

One of the first questions the students typically asked veterans was about what life was like for them before the war and how much they really knew about the war when it first began, when the United States was pledging to remain neutral.

Walter Grunden:

I think it all depended a lot on who you were, what kind of job you had, and where you lived. I think it had a lot to do with one's level of education or class and occupation.

Nick Pavlik:

For Jim Spencer of Bowling Green, the bleak economic circumstances of the Great Depression had led him to look to the military as the best option for earning a steady income. So at the outset of the war, he was already serving in the National Guard and unexpectedly found himself promoted to the rank of corporal and ready to train new recruits should the US need to suddenly begin drafting young men into service.

Jim Spencer:

The depression was a bad time for me. I was born before the depression, grew up during the depression. The military interested me primarily because it paid a little bit. I got mixed up with the National Guard here in Bowling Green with 148th Infantry in 1937 in October. And my enlistment was about to run out. Poor kid, no money, had to do something. I reenlisted in the National Guard and at that time, in 1939, it wasn't generally known publicly, but the nation was preparing for war at that time. And so I reenlisted in the National Guard. I was the buck ass private and because they were getting ready for the draft, we didn't know it at that time, but the draft occurred shortly thereafter, which meant that the unit was going to expand. And so they needed NCOs and they decided I'd make a good corporal so I sewed the stripes on.

Nick Pavlik:

For others like Allie Schrader of Belle Center and Pete Simon of Custar who had spent their entire lives in rural Northwest Ohio. The war seemed a distant concern.

Allie Schrader:

Well, I was born in Hardin County, lived on a farm all my life. And then I went to work at a little factory in Belle Center, which was called the sugar plant, made milk sugar out of milk. And that's where I made my money when I was a school boy at home.

Alexis Osborn:

What were you doing before you went into service?

Pete Simon:

I was a farmer. I was working with my dad. That's where I grew up there in Custar, Ohio, about 15 miles west of Bowling Green. I worked on a garage in the wintertime. In the summertime, I helped my dad there on the farm.

Walter Grunden:

So I think your typical person in Bowling Green, for example, or resident in Wood County, a farmer somewhere, they're probably not very tuned into what's going on in Europe. Pacific is even... Could be the moon as far as they're concerned. But I think that people in the cities, certainly people in the capital were more attuned to international affairs. They had foreign investments after all, right? And so they were concerned, "Well, okay, how is what Hitler is doing going to affect my stock portfolio with IBM," or something, right? So in that regard, maybe you could say the elites of the US were more in tune to what was going on in Europe and in Asia.

Nick Pavlik:

Another reason most Northwest Ohioans would've known comparatively little about the war was because the news media environment of the period was vastly limited compared to that of today, especially for those living in the rural Heartland.

Walter Grunden:

We have to remember that in 1941, although television technology had been invented, it was around, it was not widely available, and it was not commercialized at this point. So there were no televisions really to speak of. Most homes, people got their news from the radio or newspapers. And so there was a very limited media venue through which they could get their information. So we think about how media can be manipulated today. Just think about how easy it would have been to control the narrative and control the message if you control radio and the newspapers.

And yes, there are many newspapers: national newspapers, local newspapers, city newspapers, and so forth. But most of them are getting information from the main wire sources, the UPI or AP, or something like that. So we have to remember the media is very different. For a lot of these people, they're not able to get information beyond what's in the radio or in the newspapers.

Nick Pavlik:

Allie Schrader, for instance, remembers that when World War II began, his family's primary means of accessing the news was through a battery powered radio.

Allie Schrader:

No television at that time, or at least we didn't have any television. And if I remember right, we didn't have electric at that time. All you had was radio and a lot of them were battery operated radios. You weren't up on the news like you are today. Today, you live it. Then you found out about it.

Nick Pavlik:

And for many rural Americans, the information they were able to get about the war along with the not too distant memory of American casualties in World War I made it very clear that the war was not something they wanted the United States to become involved in.

Walter Grunden:

Something that generally doesn't enter the mainstream narrative about World War II and thinking about it what did the average American think about the circumstances? I think given World War I and the American experience in World War I, most Americans just didn't want anything to do with it.

Allie Schrader:

There was a lot of discussion and a lot of talk, a lot of worried about going into the war, but I don't think the people weren't really upset about it. They were concerned, but I don't remember anybody being really excited about the possibility of getting into war at that time. They knew it was possible, but they were hoping that Germany would get whipped before we had to go help.

Walter Grunden:

Europe, who cares? It's their problem. We had to go bail them out once before. We paid a heavy price for it. We don't need to go into something like that again. Hitler who cares? I mean, you got Stalin, which one is worse, who knows? So let them work it out, let them deal with it, just leave us alone and good to have two oceans as a buffer. So I think most people had that isolationist sentiment and just mostly wanted to be left alone.

Speaker 7:

Hello NBC [inaudible 00:17:14], Honolulu, Hawaii.

Nick Pavlik:

But that all changed on Sunday, December 7th, 1941.

Speaker 7:

We have witnessed this morning, the distance view [inaudible 00:17:36] battle off Pearl Harbor and a severe bombing on Pearl Harbor by enemy planes, undoubtedly Japanese.

Speaker 8:

The National Broadcasting Company presents H.V. Kaltenborn, Dean of Radio Commentary, who today will analyze and interpret the day's startling news from the Pacific.

H.V. Kaltenborn:

Japan has made war upon the United States without declaring it.

Speaker 9:

Here's a bullet which has just come into the unleashing newsroom in New York.

H.V. Kaltenborn:

Airplanes, presumably from aircraft carriers have attacked the great Pearl Harbor naval base on the island of Oahu.

Speaker 10:

Japanese bomb killed at least five persons and injured many others pretty seriously in a surprise morning aerial attack today on Honolulu.

Nick Pavlik:

In the early morning hours in Honolulu, Hawaii, Japan, which had been militarily expanding its empire throughout the Pacific launched a surprise attack on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor. News of the attack gradually spread throughout the continental US, causing shock, confusion, and uncertainty.

Walter Grunden:

So in a lot of these folks, when they first heard about Pearl Harbor, it was word of mouth. They had just come out of church or they had just come out of the theater or somebody said, "Did you hear? Did you hear?" And this is how they heard about Pearl Harbor.

Allie Schrader:

We got a sudden jolt and this was mouth to ear from everybody. Like I said, there was no television. Things didn't travel as fast as they do now.

Nick Pavlik:

John Andryc of Rossford and his wife Anne recall the moment they found out about the attack on Pearl Harbor.

John Andryc:

We came home from church that morning, right?

Anne Andryc:

Yeah, after... Well, around one o'clock we heard.

John Andryc:

And then we got the news on the radio that Pearl Harbor was bombed.

Jason Gray:

How did you learn that the US was in the war? Was that just [inaudible 00:19:23]-

John Andryc:

After President Roosevelt made his speech.

Franklin D. Roosevelt:

Yesterday, December 7th, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the empire of the Japan.

Walter Grunden:

Of course, everybody went to the radio as soon as possible and sat down in front of the radio, and started tuning in just like we all did when 9/11 happened. We were all glued to the TV for the rest of the day or the rest of the week, trying to figure out what was going on. They were glued to the radio and in that regard as well. So it had an enormous impact, and keep in mind, this is not long after Orson Wells broadcast War of the Worlds based on HG Wells, in the 1930s, and how that led a minor panic across the US.

Orson Welles:

Of the creatures in the rocket cylinder had Grovers Mill, I can give you no authoritative information, either as to their nature, their origin, or their purposes here on earth. Of their destructive instrument, I might venture some conjectural explanation. For want of a bitter term, I shall refer to the mysterious weapon as a heat ray. It's all to evident that these creatures have scientific knowledge for an advance of our own.

Walter Grunden:

So I think that might have been fresh in some people's minds as well. Is that, "Okay? Is this for real or not? What is really happening here? Is this Orson Wells punking us again?"

Nick Pavlik:

Temporary chaos and confusion over the Pearl Harbor attacks also beset the armed forces in the continental US. Stationed at the time at Camp Shelby, Mississippi for his position in the National Guard, Jim Spencer recalls learning of the Pearl Harbor attacks at a rather inopportune moment and the chaotic response the attacks triggered at Camp Shelby.

Jim Spencer:

I was on a date with the young lady in Vicksburg, Mississippi when the Japanese decided to tear things up at Pearl Harbor. So all leave passes, furloughs were canceled and all of us were ordered back to Camp Shelby. I got back to the unit. The place was in an uproar. All those GIs all had a rifle, but no ammunition. Everybody wanted ammunition. You would have thought the Japanese were coming down the big-

Matt Gamber:

Right there.

Jim Spencer:

… street, right there. All the time getting things straight. When I left Vicksburg and the young lady, I haven't seen her since.

Walter Grunden:

And remember Hawaii was not yet a state. Becomes a state in 1959. At that point, it's an American territory of trust. Had been its own country and we colonized it and so forth. And so probably a lot of Americans couldn't have even found Hawaii on a map, but once the Japanese attacked, most people said, "I got to go enlist. I got to do my part. It's my patriotic duty. This is my nation, my country, and you don't mess with this," right? So I think that really changed the attitude literally overnight.

Allie Schrader:

After the attack of Pearl Harbor, everybody got patriotic. Everybody was ready to join the Navy or the Army or the service. The young boys were ready to go. And it was a war effort then.

Walter Grunden:

And that's something the Japanese weren't counting on. They were really expecting the Americans to say, "Oh, we took a big hit. We'll come to the negotiating table. We'll drop a treaty. We'll stay out of the central and Western Pacific." That's what they're really counting on. We knock them out at Pearl Harbor and then the Americans are going to stay out of it because they don't have the stomach for war. They underestimated. Terribly underestimated.

Nick Pavlik:

With resolve in the wake of the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, Americans confronted the grim reality that the United States could no longer be a neutral party in the war. On December 8th, the United States declared war on Japan. On December 11th, Japan's allies, Germany and Italy, declared war on the US and the US responded in kind with its own declaration of war against Germany and Italy. The United States was now fully a combatant in World War II and immediately began to mobilize its population for war.

Speaker 11:

And the beat of feet sounds over the land. Feet intent on planning, ongoing fit for whatever destiny holds ahead. Heroes, everyone. Heroes by the million. Men who abandon form and vocations, that they may be ready to defend democracy if necessary. Certainly of body, firm in spirit. Seaman, marines, soldiers, and flyers, a huge civilian army joins in this great defense program. Rigid, rough work this training...

Nick Pavlik:

Across the US, millions of young men and women rose in defense of their country and entered into the various branches of the military. Some like Allie Schrader rushed with determination to enlist as soon as they were eligible.

Allie Schrader:

I joined the Navy. I think it was November of '44. I tried to enlist about three months ahead of that, but when I went for my physical, I chewed my fingernails. My fingernails were shorter than... And they wouldn't take me. They said, "No, you're too nervous." He said, "The only way we'll take you is if you come back in 30 days and you have fingernails. We will take you into service." I come home and I've never chewed my fingernails since then.

Nick Pavlik:

Others like John Andryc, Pete Simon, and Gordon Domeck of Wauseon simply waited to inevitably be drafted into service.

John Andryc:

I was drafted May 27th, 1942.

Jason Gray:

Okay. And what branch did you join?

John Andryc:

Army. US army.

Jason Gray:

And how old were you then?

John Andryc:

22.

Pete Simon:

Inducted into the service, 15th of December 1942. I was drafted from Wood County there where Bowling Green is and placed in the entry and service in Toledo, Ohio. I was about 20 years old.

Gordon Domeck:

I was drafted by the Fulton County, Ohio draft board in Wauseon and was inducted into the US army on June 1st, 1943.

Nick Pavlik:

Once inducted into service, our veterans were sent off to basic training camps, mostly in the American South, where they were prepared for the physical and mental demands of military service and developed lasting bonds with fellow servicemen from across the country.

Walter Grunden:

When you talk to the veterans, so often what they will recall first off is basic training.

John Andryc:

I was inducted at Camp Perry. Got my basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky.

John Damman:

We took our basic training at Camp Robinson, Arkansas, close to Little Rock.

Gordon Domeck:

I was sent to Camp Fannin near Tyler, Texas for infantry basic training.

Allie Schrader:

I went to Great Lakes Naval Station in Illinois.

Pete Simon:

Took our basic training, started at Camp Wood, Texas.

Jim Spencer:

Shelby, Mississippi, which was a wide open, flat space full of brush and whatnot and nothing but tents, and big pits dug in the ground for a latrine with a wooden box put over. I don't know whether you're familiar with those or not, but I am.

Walter Grunden:

The camaraderie of boot camp.

John Damman:

We had six man huts we called them. There were six guys in a building. There were just small buildings and we had to fall out every morning. In the evening, we had to run a mile about every day.

Walter Grunden:

Running up that hill every day to build their physical fitness, but also mental fitness as well to mental training.

Gordon Domeck:

That tough military training turned a soft high school student into a hardened young man.

Allie Schrader:

It was strictly teaching you discipline. You knew you had things to do. You had a certain time to do it and you best be on time.

Walter Grunden:

Having a drill instructor who was just an absolute... Can I say son a bitch? I mean, it isn't family-friendly, but.

John Damman:

Whenever anything went wrong, why they kept us coming out, maybe till two, three o'clock in the morning. And we had to fall out and the rank and the sergeant would dismiss us. And pretty soon he'd blow the whistle and I had to fall out again until somebody come up that did something wrong.

Walter Grunden:

The relationships that they forged at that time, they'll never forget those people. They see them at reunions and they stay in contact for decades after.

John Andryc:

Tony Wojinksi. Yeah, in Richeyville, Pennsylvania. He calls about every... We talk to each other about every other week or something like that.

Gordon Domeck:

We have a quarterly newspaper that keeps in contact with our buddies. Just recently I noticed on that paper, a death of a member of my platoon, his nickname was Coy, and he always sent me a birthday card for he too remembered our first day in combat.

Walter Grunden:

And the other thing is his food, just how bad the food was.

Allie Schrader:

We run out of food once and we ate cornbread and beans for about three months. We ate that three times a day. That kind of... I don't eat beans today.

Nick Pavlik:

The conditions of basic training may have been harsh, but they were necessary to truly prepare young servicemen to meet the unforgiving realities of combat that awaited them in Europe and the Pacific.

Gordon Domeck:

Training for combat is where service to our country really begins, in my view. Without adequate training and good equipment, victory is uncertain and much manpower is lost. An untrained division is going to have a lot more casualty than a well-trained, well-disciplined division.

Nick Pavlik:

The basic training our veterans received also differed depending on which branch of the armed forces they had entered into.

Walter Grunden:

People were trained according to the needs of the different services. So if you're going into the Navy, of course, you had to know how to swim. And if you didn't know how to swim, maybe they would make you a Marine instead or something. But Navy always transported to Marines. If you absolutely couldn't swim, maybe you would, pun intended, would wash out. Maybe they would put you in the Army or something like that. But it all, depended on the service that you had either tried to get into. Sometimes you could ask to go into a certain service and maybe you would get that. Other times, maybe you would just be assigned to service.

Nick Pavlik:

John Damman of Napoleon and Gordon Domeck, both of whom were drafted into the US Army Infantry, recall some of the specific activities involved in basic training for infantry men.

John Damman:

We had to take a rifle, go out to the rifle range, wherever we went while we had a walk. And usually, you had a full field packed with you. And we went out to the rifle range to shoot targets.

Gordon Domeck:

We had to take special training, combat training. And I was shipped to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana as an infantryman in the 84th Division. We trained in the hot and humid swamps of Louisiana and became a well-trained and cohesive combat unit.

Walter Grunden:

But there are a lot of variables in terms of not only what service one was in, but also what you ended up doing in that service. If you had certain skill set that you had to offer, that could also determine where you ended up like the one interview we listened to...

Nick Pavlik:

Dr. Grunden is referencing Pete Simon's interview here.

Walter Grunden:

The guy talks about how he was a mechanic and he worked on the farm, fixed the tractors, but in the wintertime, when you couldn't farm, he worked in a garage and he fixed cars. So he ends up being in a tank core so he can fix tanks. He's a mechanic so that's a transferable skill.

Pete Simon:

Since I had worked as a mechanic there in Western Ohio in the winter months, the Army checks your record, and they found out that they needed some mechanics in the tank outfit. So I was one on the pick to going down to Camp Hood again. And I went to three months of schooling down there to learn more about mechanics working on tanks and so forth. You take some training on driving the tank, how to drive them in mountainous territory or through mud or whatever it is. And trying to let you know that a tank can get stopped too, the same as a vehicle. So make sure that you try to find the best ways of driving a tank. And then you want to be able to drive the tank so that you can see that so if there's a target to fire at, you can line up so that the gunner can get a shot at the target, so.

Nick Pavlik:

As Dr. Grunden notes, it's also important for us to remember that while many young Americans who went through basic training, went on to engage in actual combat during the war. Even more served in non-combatant positions that while not on the front lines were no less crucial to American military operations during the war.

Walter Grunden:

Often, when we think about World War II, the narrative almost always focuses on combat and those guys up front, but they were really, in terms of the vast numbers of people who served, they were actually smaller in number than all of the other people who worked behind the lines in support positions. To get working logistics, to get the equipment, to get the food, to get the water, get the ammo, everything up to these guys who are doing the combat. The vast majority of people who served were actually in these kind of support positions and not actually on the front line. And we hear a little bit of that in these interviews too. Well, the one guy...

Nick Pavlik:

Here Dr. Grunden is referencing John Damman.

Walter Grunden:

He talks about how he was sworn in. He was inducted like 20 minutes before the war ended.

John Damman:

Well, it was about 20 minutes before the war ended. I got sworn in.

Walter Grunden:

So what did he end up doing in the war? Well, nothing really, but after the war, he re-strung power lines across Germany. So fascinating in its own right, but those are the stories we don't hear. Again, which to me speaks to the value of oral history and doing these interviews and having these interviews, because again, it can personalize the war and we can understand it from the ground up.

Nick Pavlik:

While John Damman service was dedicated to rebuilding projects after the war, our other veterans, John Andryc, Gordon Domeck Allie Schrader, Pete Simon, and Jim Spencer were sent at the height of the war into the European and Pacific theaters where brutal battles of unimaginable intensity between Allied and Axis forces were raging on land, at sea, and in the air and where they would all play their part in furthering the Allied military advance in some of the most decisive campaigns that help determine the outcome of the war. Dr. Grunden's expert knowledge of the war provides crucial historical context for these campaigns and the experiences of our veterans within them.

Walter Grunden:

Well, maybe we should start with what maybe most people today might know about the war. They might think they know about the war and how that comes to us. And that typically has come to younger generations through Hollywood and what Hollywood has focused on or chosen to focus on.

Nick Pavlik:

And more often than not, that focus tends to be on the American involvement in Western Europe, beginning with the D-Day invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

Walter Grunden:

But I think Americans connect with that because that in the mainstream narrative is when many people really feel like America had arrived and we really got into the war. Well, of course we were in Africa already, invading Northern Africa and trying to push the Germans and the Italians back. And so long before D-Day we were fighting in Africa and we were fighting in Italy, took Sicily, tried to go up the boot and into Italy. And of course, we were in the Pacific right away.

Speaker 12:

America goes to war. Men of the Army, Navy and Marines, battlefronts on six continents to save the homes and ideals of free men from Axis domination.

Nick Pavlik:

Jim Spencer's 148th Infantry regiment was sent into the Pacific in the spring of 1942 to confront Japanese forces that had by then ceased control of vast amounts of territory in the Pacific and built up a defensive perimeter stretching from Western Alaska to the Solomon Islands.

Jim Spencer:

In short order, we were put aboard at troop train and I wound up in San Francisco in April 1942, boarded a troop ship, the Santa Lucia. Jesus Christ what a boat. God damn scowl. It was later sunk in the North African campaign and I wasn't a bit sorry. And we sailed aboard it and into the Pacific. Of course, in those days, you didn't bother to tell you a damn thing that you didn't really need to know. All we knew was we were going into the Pacific.

Nick Pavlik:

While Spencer's regiment sailed into the Pacific, Allied forces led by the United States, achieved two major victories against the Japanese that began to turn the tide of the war in the Pacific in the Allies favor.

Walter Grunden:

You have the battles of Coral Sea, in which the Japanese lose one carrier and another is damaged. And then Midway in June '42, where they lost four aircraft carriers. Midway was a complete debacle for the Japanese because they didn't realize that we'd broken one of their military codes. And so we knew basically exactly where they were coming and what they were bringing with and were ready and prepared for it. Still, a hell of a battle. Still very costly, but in the end, they lost four aircraft carriers, which they could ill afford. Then that pretty much, it didn't quite break the back of the Imperial Japanese Navy at the time, but it was a huge setback they never recovered from. So from that point forward, they were always on the defensive in the Pacific.

Nick Pavlik:

In early June 1942, Spencer's regiment landed at Fiji where they began preparing defenses for an anticipated Japanese assault.

Jim Spencer:

We got into the heart of Suva in the Fiji Islands. And the next day when it got daylight, we went around to a little place called, a little town on the Vita Levu called Nadi. Got off the ship, went inland and proceeded to start digging foxholes because the Japanese by this time had taken several islands. They owned the Solomons, they'd been in Burma, and they figured that the Japanese were going to jump on the Fiji Islands. So we started to set up the defenses in the Fijis.

Nick Pavlik:

Spencer's regiment would play a critical role in what became known as the Allied island hopping strategy in the South Pacific, which under the command of US General Douglas MacArthur was designed to isolate Japan's most heavily fortified islands while also drawing resources away from their defenses in the central Pacific.

Walter Grunden:

Admiral Nimitz, from the beginning, he wanted to go pretty much straight up the central Pacific and take these small islands as forward air bases and bomb Japan as much as they could, soften them up, and then prepare for a land invasion. They would land in Kyushu, the southern most island and then they would also hit Honshu and try to drive on Tokyo. Now that's the most direct route and probably you might think it might have been the more simple of the objectives to achieve in that regard, but if they had done that and only that the Japanese could have fortified much more strongly along the way and made that strategic approach very, very difficult, if not impossible. MacArthur who had an affinity for the Philippines and the people of the Philippines, it had been... He was ordered to leave as the Japanese had invaded Philippines early in '42. He said, "I shall return."

He wanted to get back to the Philippines. His idea was that we take a two-prong approach, that we follow Nimitz's strategic approach, but also go into the Western Pacific and go island hopping through the Western Pacific and engage Japan, particularly like in the Solomons and New Guinea and trying to bypass the most fortified islands and positions. Go around them, take positions behind disrupting Japanese supply lines and so forth, and then starve them out. So it became a battle of attrition along the way so that you would block them from invading Australia, which they were driving and intending to do. And again, to drain resources away or pull resources away from Japan's defensive perimeter in central Pacific.

Nick Pavlik:

In August 1942, the Allies launched their first island hopping offensive against the Japanese with the battle of Guadalcanal. Commencing the Allied campaign to take the Solomon Islands from the Japanese.

Speaker 13:

Guadalcanal Airport, the tiny patch of land for which Japan has sacrificed a fleet of warships and thousands of fighting men still bristles with United States bombers. For the forces that controlled Guadalcanal, command the approaches to Australia. Pulled mastery of the skies over the vitally important Solomon Islands. Today, these land based bombers are leading the way as the combined United States land, sea, and air offensive...

Walter Grunden:

Guadalcanal. That's the first time that we actually retook land territory back from the Japanese, not just sea lanes and so forth, but territory.

Jim Spencer:

The Navy, along with MacArthur and a few other people, they decided to take Guadalcanal away from the Japanese because they had started a field, an airfield on one end of island called Henderson field. The Japanese didn't realize that the United States and their allies had the forces or the means necessary to jump on that island and give them a bad time. It kind of took him by surprise. I didn't do any fighting on Guadalcanal. I got there after the last shot had been fired. But anyway, we horsed around there on the island and done some additional training.

Nick Pavlik:

From Guadalcanal, Spencer's regiment then advanced further into the Solomon Islands.

Jim Spencer:

Our next mission was headed for New Georgia, which is also an island in the Solomon group. New Georgia had already been invaded, but the forces that were ashore needed a lot of help. My division was selected to help those people. So we got there at night and boy was that dark and no lights. But we got ashore and got into the fight and took the island away from the Japanese. And from there, we went back to Guadalcanal, cleaned the weapons, got a few replacements in for the men that we had killed and wounded, and done some more training. Got the regiment ready and the rest of the division and decided to take Bougainville, which is also a part of the Solomon Islands. I believe it was on around the 5th of November that we got there of 1943 on Bougainville. We went ashore. My company was on an outpost where the Rewa River emptied into the Pacific Ocean on Bougainville.

And the Japanese had tried to make a... Sent some reinforcements in down there and we had to wreck them. So they sent the company up there to establish an outpost; a patrol base. The Japanese had lost some boats. Their invasion craft they used to move troops around those islands were a foldable-type craft. They had some excellent outboard engines and a friend of mine in the heavy weapons support platoon in the company I was with was a pretty fair mechanic and we got... Those engines had been left on shore and the boats. So we finally got one of those big engines to run. We got one of those boats and got it unfolded and put it in the ocean and hung that engine on it, and we run up and down to get our supplies and their ammunition and whatnot while the rest of division established the main line of resistance and tied in with another division and we built an airfield on Bougainville. Hell I was up there three, four months. Well, we had a couple bad fights on Bougainville.

Nick Pavlik:

By mid-1944. American-led Allied forces had largely rested control of Bougainville from the Japanese. Marking the beginning of the end of the Solomon Islands campaign. The Allies in the south Pacific could finally set their sight on retaking the Philippines. The island hopping strategy was working, but it had also come at a horrendous cost.

Walter Grunden:

So although some people have criticized MacArthur saying, we really didn't need to go into the Philippines just yet. And it was maybe too much of a diversion of resources for us. It was even a greater diversion of resources for the Japanese. So was it the best move? I don't know. I mean, historians are still debating that. I mean, US Marine Corps paid a tremendous price. We lost a lot of Marines along the way.

Nick Pavlik:

While Jim Spencer was engaged in combat in the Solomon Islands, two of our other veterans, Pete Simon and John Andryc, both of whom had been assigned to armored tank units bound for the European theater were being prepared to cross the Atlantic.

Pete Simon:

And I ended up in what they call a 610 Tank Destroyer Battalion. And so they figured that since I knew something about the tanks that they were going to put me in the tank and using me as a driver.

John Andryc:

I was in Patton's Third Army, Twentieth Corp, Seventh Armored Division. 434th Armored Field Artillery. Now, that's a tank, we fired direct fire and indirect fire.

Pete Simon:

We were attached to the 80th Infantry Division and wherever they go, we were supposed to supply the armor.

Nick Pavlik:

The Allies were preparing to launch their assault on German-held Western Europe commencing with the D-Day invasion of Normandy on June 6th, 1944.

Pete Simon:

So we boarded the ship and we left New York the third day of June in 1944. Went on out into the ocean and headed east, headed for Europe. And we were just out in the middle of the ocean on June the sixth, when the D-Day was in Europe.

Speaker 14:

Now the signal from the flagship.

Speaker 15:

All hands to beaching stations.

Speaker 14:

All hands to beaching stations. That's the signal for our sailors on board this craft to get ready for the landing. And of course, for the soldiers down in the holes to get ready with their [inaudible 00:48:19] under of the deck and down the ramp as we go into shore.

Speaker 16:

BBC home service. D-Day has come. Early this morning, the Allies began the assault on the Northwestern face of Hitler's European forces. The first official news came just after half past nine when Supreme headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force issued communiqué number one, this said, "Under the command of General Eisenhower, Allied Naval forces supported by strong air forces began landing Allied armies this morning on the Northern coast of France."

Dwight D. Eisenhower:

Soldiers, sailors and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force. You are about to embark upon the great crusade toward which we have driven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave allies and brothers in arms on other fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe and security for ourselves in a free world.

Pete Simon:

When we were going across the ocean, our boat zigzagged all the way across the ocean to keep away from submarines that might want to blow us up you see. Because the Germans had a lot of submarines out there that was trying to blow up a lot of the ships, but ours didn't get blown up. We ended up over there in good shape. So when we landed in Glasgow, we were lucky to get there. And we landed on the 12th day of June 1944.

John Andryc:

Got on the Queen Mary, went over and into Scotland, Glasgow and from there to the barracks.

Nick Pavlik:

Both Simon and Andryc would take part in the allied charge into France after D-Day.

Pete Simon:

Just before we went over to France, we went on down to Wales to practice our guns to make sure that they knew the equipment was good. So they have targets out there in the ocean. And we fired at these targets to make sure that the guns were lined up with the sites and everything.

John Andryc:

And then across the channel and to Utah Beach.

Pete Simon:

Shortly after that, we headed out and went to Northern France.

Walter Grunden:

After the D-Day, Normandy invasion, they capture the beach and then they're moving inland. And that's when we have the major land battles in Europe that most Americans will know.

Nick Pavlik:

In part two of this three part episode, we'll follow our veterans as they fight their way further into the European and Pacific theaters. And the Allies begin to close in on Nazi Germany and the empire of Japan.

Archival Encounters is produced by the Center for Archival Collections at Bowling Green State University libraries. Special thanks to our featured guest, Dr. Walter Grunden of the BGSU Department of History and to Marco Mendoza of the BGSU School of Media and Communication for his assistance with audio production.

Additional credits are available in our show notes. To access the entirety of the History 303 Oral History Collection and to learn more about the Center for Archival Collections, visit our website at bgsu.edu/library/cac.

- Featured Guest: Dr. Walter Grunden, Professor, BGSU Department of History

- Host: Nick Pavlik, Manuscripts and Digital Initiatives Archivist, BGSU Center for Archival Collections

- Producer: Pavlik

- Engineer: Marco Mendoza, Media and Technology Specialist, BGSU School of Media and Communication

- Editor: Pavlik

- Script: Pavlik

- Music: Connor McCoy, BGSU College of Musical Arts alumnus; Blue Dot Sessions (“Blue Wind Blow,” “Delving the Deep,” “Flashing Runner,” “Idle Ways,” “The Onyx,” “Pintle,” “Silent Ocean,” “Tumblehome,”); Gregor Quendel (“Cinematic Orchestral Arpeggio Sketch,” “Cinematic Percussion Sketch”). All music licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0 and CC-BY-ND 4.0.

- Archival Audio: History 303 World War II veteran oral histories; “1939-09-01 BBC Alvar Liddell Reports the Invasion of Poland”; “1939-09-01 CBS Adolf Hitler Announces War with Poland”; “1939-09-01 Polish Ambassador to US on War with Germany”; “1939-09-02 Chamberlain Declares War”; “Franklin Roosevelt’s Fireside Chat After Germany’s Invasion of Poland”; “December 7th (Short Version)”; “News Flash Describing the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor, 12-07-1941”; “H. V. Kaltenborn's Analysis Of The Japanese Attack On Pearl Harbor, 12-07-1941”; “President Franklin D. Roosevelt Declares War on Japan”; “War of the Worlds Remastered 1938 Broadcast”; “America’s Call to Arms”; “News Parade of the Year 1942”; “November 1942 News Reel”; “1944-06-06 BBC Robin Duff at Signal for Landing”; “1944-06-06 BBC John Snagge D-Day Has Come”; “1944-06-05 Eisenhower’s Pre D-Day Announcement to Troops”

Episode 1: Ella P. Stewart, Civil Rights Trailblazer of Toledo

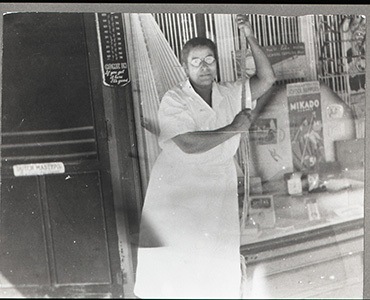

In our first episode of Archival Encounters, we feature an oral history interview recorded in the 1980s with Toledo pharmacist and activist Ella P. Stewart, and speak with Dr. Shirley Green, adjunct instructor in the BGSU Department of History, about Stewart's life and legacy. One of the first professional Black female pharmacists in the United States, Stewart operated a neighborhood pharmacy that was a central fixture of Black life in Toledo during the early and mid-twentieth century. Throughout and beyond her pharmacy career, Stewart was also a recognized leader in civil and women's rights activism at the local, national, and international levels and served in prominent roles in numerous advocacy organizations.

In our first episode of Archival Encounters, we feature an oral history interview recorded in the 1980s with Toledo pharmacist and activist Ella P. Stewart, and speak with Dr. Shirley Green, adjunct instructor in the BGSU Department of History, about Stewart's life and legacy. One of the first professional Black female pharmacists in the United States, Stewart operated a neighborhood pharmacy that was a central fixture of Black life in Toledo during the early and mid-twentieth century. Throughout and beyond her pharmacy career, Stewart was also a recognized leader in civil and women's rights activism at the local, national, and international levels and served in prominent roles in numerous advocacy organizations.

Nick Pavlik:

From the Center for Archival Collections at Bowling Green State University Libraries, this is Archival Encounters, where archives come alive and past voices meet our present moment. The Center for Archival Collections, or the CAC, collects, preserves, and provides public access to unique historical records documenting BGSU, the Northwest Ohio region, the Great Lakes, and National Student Affairs, as well as an extensive rare book collection.

I'm Nick Pavlik, an archivist at the CAC. And in this podcast, we'll be sharing some of the captivating stories that our archival collections have to tell, from those that have loomed large in local histories to those that have been long forgotten. We'll be especially focusing on oral histories, recorded personal remembrances of historical and biographical events as told by those who lived them.

Ann Bowers:

You moved to Toledo in 1922. What made you move to Toledo?

Ella P. Stewart:

Well, I understood there was not any drugstore that was owned and operated by Negros here. I was in Detroit and I did not like Detroit so I decided to come over here one day and look it over. I came over and when I got off of the bus to go to a friend's house, which was next door to this building that we purchased here at the corner of Indiana and City Park, they were putting the for sale sign on. I went up and told them about what I wanted. I said, "They're putting a for sale sign on the building and I'd like to see that building." Then, we went down and looked at the sign and we looked around. I liked it very much because it had cement floors and a steel ceiling. It was a big building and it had nine rooms above the drug store. I said then, I'd bring my husband over in a couple of days. Of course, then he decided if I liked it and wanted it, it was all right.

Then, we decided to buy the building and we put the money down, that was on... about the 15th of April. Then July 1st, we opened up the store in Toledo. The building was really in my name, of course he had to sign for it but I owned the building and we both owned the drugstore.

Nick Pavlik:

That was the voice of Ella P. Stewart, one of the most remarkable individuals in the history of Toledo, Ohio. Shortly before her death in 1987 at the age of 94, Stewart recorded an oral history of her life with CAC archivist Ann Bowers. Stewart donated the oral history recording to the CAC, along with several of her personal papers and scrapbooks. Since that time, the entire Stewart collection has been available at the CAC to all who wish to see it. As we heard just a moment ago, Stewart moved to Toledo in 1922 where she established Stewart's Pharmacy in the neighborhood of Lenk's Hill. Six years earlier, in 1916, Stewart had been the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Pittsburgh's School of Pharmacy. After passing her state exam that same year, she became one of the first professional Black female pharmacists in the United States.

In Toledo, Stewart's Pharmacy became central to life in Lenk's Hill, where it operated for nearly 25 years. But, this is only one aspect of Stewart's remarkably accomplished life. Her far more enduring legacy is as one of 20th century Toledo's most pioneering civil rights activists and community leaders. To better understand the significance of Stewart's life story and the context of her times, we enlisted the historical expertise of an instructor here at BGSU.

Shirley Green:

My name is Shirley Green. I am an Adjunct Instructor at Bowling Green State University. I received my PhD from BGSU, as well. I also am the part-time Director of the Toledo Police Museum, which is located in Toledo, Ohio. One of my responsibilities as a second year PhD candidate down at Bowling Green State University... I work with a local historical society here in Toledo, Ohio.

Nick Pavlik:

Which organization was that?

Shirley Green:

It was the African American Legacy Project. We were capturing the oral histories of senior members of the African American community and what their experiences were, how they remembered the Black community that they grew up in. It's really funny because thinking back on that particular oral history project, which is in the early 2000s I believe, I remember many of them talking about Stewart Pharmacy. A lot of them talked about Stewart Pharmacy. I remember going in there. I remember sitting at the soda fountain bar. I remember getting prescriptions there. They had very fond memories of Mr. and Mrs. Stewart and that pharmacy, that pharmacy was a focal point of their community. One of the things that... you can look through all those oral histories, and that's one of the common themes that would pop up in their memories.

Ella P. Stewart:

The people there just got very fond of us because we were so much interested in their home, their children and whatnot... people had a lot of children. We got to be known as just probably a member of the Lenk's Hill group. As a Negro people began coming in, well, of course they would come from their various churches, a distance, after Sunday school or church. Of course, on Sundays we were very busy. We always had to have extra help to help serve them because we had tables in there for ice cream... drug stores had soda fountains. We had a large 16 foot soda fountain, so we had a lot of business. We kept busy and we opened up at eight o'clock and would close at 11. Sometime between 10 and 11 there were hardly anybody in the store, but we stayed open in the event they needed something. Most of it was probably cigarettes or something that they had forgotten, however... then, they could ring our bell because we lived upstairs in the nine rooms that were upstairs

Nick Pavlik:

Before listening to this interview, I had never heard of the Lenk's Hill neighborhood in Toledo. Had you heard of that neighborhood before? What can you tell us about it?

Shirley Green:

Well, I did not grow up in that area of town. I grew up in the north end, but I do know people who grew up around that area so I had heard about the term Lenk's, but not Lenk's Hill. However, having said all that, I did a little bit of research and talked to some individuals and understood that this area in Lenk's Hill... when Ella P. Stewart moved to that area... in 1922 they came here, it was primarily a German-American neighborhood. It was named after a German immigrant who started the first winery and brewery in Toledo. He purchased a block of land in that south Toledo area and started to build homes for other German immigrants to Toledo. I think they also had a park there. There was a park that was located at a period of time in the 1870s, late 1800s, that was called Lenk's Park.

Then, it would eventually become City Park, which is where the pharmacy was located there at Indiana and City Park. Toledo is... and growing up, this is the way I remember it. I don't think it's that way as much anymore, but Toledo like any other urban setting had distinct ethnic neighborhoods. You had this German-American neighborhood that grew out of Lenk's Hill. Right next to that German-American neighborhood was a Polish-American neighborhood. Then, you had pockets of Black communities and neighborhoods sprinkled throughout the city. One of the largest during the Great Migration period was something called the Pinewood District. Then, there was a community in the north part of Toledo. It is not unusual that Lenk's Hill grew out of one German immigrant and that they all collected together to make their own communities over there.

Nick Pavlik:

Contrary to what I would've expected, Lenk's Hill being a predominantly German-Irish neighborhood, she doesn't indicate that she had any difficulty at all establishing her drug store there and indicates more that she was quickly welcomed by the community and that the pharmacy was pretty successful within a short time. I was just wondering if you were also surprised to hear this?

Shirley Green:

Well, not entirely but somewhat. Listening to the history of the German-American neighborhood and the Polish-American neighborhood being right next door to each other, there were some tensions there sometimes. I was surprised to see that she was so accepted by the German-American community there.

Ella P. Stewart:

We'd open the store and we had such a crowd out there that they were lined up on both sides, on the City Park side and Indiana side to get in. 90% of the people were White, Caucasians, either Irish or German... they were Caucasians and a few Spanish people. There were not many Spanish people here then, and not many other ethnic groups here then, except the Caucasian people. But, we were busy all day long. You never saw so many flowers... we had, really, tubs of flowers, just flowers all over the place and people could hardly get around in the store for the many flowers that people had sent. It was really a wonderful occasion. In fact, one of the editors of The Blade was there, one of the reporters said that they had never seen so many flowers at an opening. I was so shocked that I said to my husband that night... we didn't get to bed until about two o'clock in the morning.

But anyway, I said to him, "Well, my dear, I hope you're pleased now." He says, "I'm not pleased until the money starts coming in." He says, "Those people are just coming in and sight-seeing." However, we opened up the store and we began to do business and we had a very good opening of the business. That was my opening of the drugstore in Toledo.

Ann Bowers:

It sounds like it.

Shirley Green:

Now having said that, maybe she was the only game in town, maybe that pharmacy was the closest one. As soon as they figured out that they were doing good work there, they could overlook some things if Mr and Mrs. Stewart were a good Pharmacist and welcoming them in their store. It was easier for me to walk down half a block to get my script than go all the way over here to get my script, so just the fact that they were there in the neighborhood could have been why she was successful.

Nick Pavlik:

Ella P. Stewart arrived in Toledo toward the beginning of what is now known as the Great Migration, in which from the 1920s to the 1970s six million Black people fled the rural south to the cities of the Northeast, Midwest, and West in the hopes of escaping the state sanctioned anti-Black racism of the south and finding better economic opportunities. Toledo was among the several Midwestern cities that Black southerners moved to during the Great Migration. I asked Dr. Green about the effects that this seismic demographic transformation had on the city.

Nick Pavlik:

What can you tell us about Toledo's place in the history of the Great Migration and what it would've been like for a Black person from the rural south arriving somewhere like Toledo?

Shirley Green:

Well, before the Great Migration there were Black communities located throughout Toledo. There were communities located near the downtown area. There was also a community in east Toledo. One of the first Black communities were located in a place called Manhattan, Ohio, which is now where Manhattan Boulevard and Summer Streets come together in present day Ohio, Detwiler Park sits there right now. But, if you're looking at the Great Migration that occurred between the 1920s, and some historians push it all the way back to the 1970s, there are three main streams of migration patterns, and it depended upon where you lived in the rural south is where you wound up in the north. The patterns that affected Cleveland, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, those individuals came from Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, as well as Tennessee and Kentucky. They're coming to the big city. What this mass migration did was... by 1920 Toledo's Black population was almost at 6,000 individuals. By 1930, it was doubled that number, it was 13,000 people. It doubled in 10 years.

Shirley Green:

You could see how rapidly the Black population grew. What they were dealing with when they came into Toledo was they... most of them had to live in an area called the Pinewood District. The major thoroughfare of the Pinewood District was Dorr street, basically the junction between present day Dorr Street and Division Streets would come together. One of the streets that a lot of folks who came up from the Great Migration lived on was a street called John R Street. Now, some of those street have been... they were destroyed basically because they had to make way for public housing complexes, which came up in the late '40s and '50s. But for the most part, Blacks who came from the south into Toledo were relegated to live in mostly segregated communities. That was done because the efforts of groups like the Citizens Realty plan. This group supported racial restrictions and property ownership, they often threatened violence against African Americans who attempted to buy homes outside of their designated districts.

They were really constrained to living in certain areas and they are also relegated to low wage, semi-skilled, and unskilled jobs. As the Black population grew as a result of the Great Migration, neighborhoods like Lenk's Hill became more diverse and more Black. What the stewards were able to see at their pharmacy was a neighborhood transition from being a German-American neighborhood, an Irish neighborhood to slowly but surely becoming more diverse and then primarily a Black neighborhood. However, they were still considered the focal point of that community, along with an area on Dorr Street that would become the epicenter of Black culture in Toledo. They were all part of that and Mrs. Stewart saw all that change.

Nick Pavlik:

In what became a common occurrence in 20th century urban neighborhoods, as more Black people moved into Lenk's Hill more and more White people who had been living there began to move out.

Shirley Green:

The original Pinewood District that was segregated off just couldn't hold the influx of new people. They started to push, and as they started to push then the German-Americans and some of the Polish-Americans... I think the Polish-Americans were the last to leave that area and the area I grew up in as well... they just started to leave. They could, not sell their homes, but rent their homes out and things of that nature.

Ella P. Stewart:

People said I was going to starve to death because I was moving in a... well, people were being transferred from one area to another, and then the folks were coming in and it was more or less of an Irish and German neighborhood. Of course, they were selling to the Negro people that could buy and move out of the Canton Avenue section and wherever they were living. It was really a venture on our part to really go into the neighborhood.

Nick Pavlik:

The Great Migration sparked Stewart's career in Civil Rights activism and community leadership. Many migrant families to Toledo, having come from the rural south, struggled to make new lives for themselves in a large Midwestern city. Stewart, being as immersed as she was in her community, witnessed these families struggles firsthand and was moved to help. She became a member of the Enterprise Charity Club, a women's philanthropic organization that provided assistance to migrant families and welcomed them to Toledo.

Shirley Green:

Where do those people work and where do those people go? And organizations like Mrs. Stewart's Enterprise Charity Club help these women who were coming up from the south, never lived in the city before, helped them to understand what they needed to do, where they needed to go, who they could count on to help them, what resources were there.

Ann Bowers:

This Enterprise Charity Club was a women's club, right?

Ella P. Stewart:

It was just a women's club, it was one of the leading charity clubs among Negro's in the city of Toledo. They were doing charity work because there were so many Negro people that were coming from the south that didn't have anything because the various firms were going down, bringing them up, and just giving them probably a place to stay, or big families would be... maybe two or three families in one place. As people would move out, they would rent to them and get the rent. People began to buy in the neighborhood and whatnot, but they're the ones that would go and get baskets of food if they needed food. They would go in and tell them, let's see it there. Some of them... down south they didn't have to have windows, like shades and things like we have here.

They'd have newspapers up. We'd go and get them some curtains and show them how to make the curtains, or else make them form them and take them and put them up, show them how to do the things... the women from the charity club. I was not the only one there was, many of the women did that type of work. Those that weren't working, not that too many of them were working, they were more housewives, they could do it very easily. But, I began to work with them, getting them leadership because they had not been... some of them had worked on the farms. They didn't know how to cut the grass and the weeds and things.

Shirley Green:

It's always interesting to me how these women groups also want to tell you how to keep your house. We're going to find some curtains for you. We're going to do all these things. I think it probably was helpful to these women because they just wanted to be accepted, I'm sure. These are the little things that Mrs. Stewart and others tried to give them. They had teas, they had parties, they had contests. They did all of the Christmas parties. They did all of these things to make these women feel, and their families feel, welcome. That was very important to her. It really was.

Nick Pavlik:

The Enterprise Charity Club marked the beginning of an illustrious career in activism and philanthropy for Stewart. Having been recognized for her leadership in the Enterprise Charity Club, in 1944 Stewart was elected President of the Ohio Association of Colored Women. She was then elected President of the National Association for Colored Women, a role she served in from 1948 to 1952.

Shirley Green:

The National Association for Colored Women, what an amazing group and collection of people. But to understand that group, you have to understand the women's club movement that originated in the late 19th century, early 20th century, among upper and middle class women. They were trying to provide a way for women to improve their own lives through education and to improve their own communities through public service. They were also trying to help the lives of poor women that lived in their communities. These clubs started to work on a number of issues. Some of these local clubs opened private libraries, which were eventually taken over by local governments. Some of them even expected schools, they lobbied for building playgrounds, they campaigned for kindergartens in preschool, and they brought in nurses and hot lunches into schools, especially the schools where poor children were attending.

Then, some of these club women also fought to improve sanitation and public health services. They did a little bit of everything, and this is in the late 1800s, early 1900s. Eventually, these individual groups would come together under a national umbrella. In 1890, they formed something called the General Federation of Women's Clubs. These were mostly White women in their local White clubs, but there was a parallel kind of movement going on as well among the African American community. The African American groups, the local groups like the Enterprise Charity Club, they were also dealing with the same type of issues that the other women's clubs were dealing with, but they're also dealing with issues of race. They were dealing with issues of education and community improvement, but also how race affected all of those things for Black children and Black families.

One of the founding members of the Black woman's club movement was a woman by the name of Mary Church Terrell. She's also a friend of Mrs. Stewart, there are several pictures of her and Mrs. Stewart together in Ella P. Stewart's collection. So, like the White counterpart group, the Black women's club movement also started their own national organization in 1896. That was the beginning of the National Association for Colored Women. That first version, the founding members were... listen to the names of these founding members, and this was pre Ella P. Stewart, of course, because they were formed in 1896. Harriet Tubman was a founding member, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a founding member, and Mary Church Terrell was a founding member. The original motto, and I think it is still the motto of the association was "Lifting as we climb".

They focused on child care, fairness in wages, education, and they raised money for libraries and retirement homes. They were also very strong advocates for the anti-lynching campaign because if Ida B. Wells-Barnett is involved, they're going to be a strong advocate for the anti-lynching campaign. They also fought against segregation in public transportation, public accommodations, which Mrs. Stewart would be involved in on a local and a national level. When she became president in 1948, she served a four year term and she took over all the responsibilities that Mary Church Terrell and others had before her. It's really interesting if you look at any of the histories or any writings about the National Association for Colored Women... and they eventually added clubs to their names, and you read about Mary Church Terrell and some of the other organizers and founding members and other presidents that were very impactful during their term.

You don't read a lot about Ella P. Stewart, which has always been very surprising to me that more people haven't latched onto her story. She really needs to be recognized, concerning her work as president of that association. One of the things that Mrs. Stewart had the responsibility of was the maintenance of the Frederick Douglas... his last homestead. It's a historic site and that association took over its maintenance and upkeep, they actually purchased it to make sure that it maintained a historic site. It wasn't until the 1960s that they turned it over to the National Park Service, and now the National Park Service runs it as a historic site. She was also president when they were organizing campaigns against segregation on public transportation. During her presidency, the group lobbied effectively for many progressive measures. They lobbied for the passage of an anti-lynching law, an anti poll tax law, fair housing, fair employment practices. They also supported Black-owned businesses, as well. They established scholarship funds for young Black women. When she was president of the organization, she did a number of things. She's amazing.

Nick Pavlik:

As Dr. Green notes, the National Association for Colored Women played a significant role in the larger history of the Black freedom struggle, one that has still been under-acknowledged.

Shirley Green:

This is a precursor, all of the stuff that she and these club women were in and members, these individual associations that were members of the national group, they're all precursors to the Civil Rights Movement of the late 1950s with the Montgomery bus boycott. The Civil Rights leaders were able to plug into all of these other things that were going on before there was a major push in the '60s.

Nick Pavlik:

Though she became recognized at the national level for her Civil Rights work, Ella P. Stewart maintained a deep commitment to her home community of Toledo. In 1961, she became a founding member of the Toledo Board of Community Relations, where she fought for fair employment and fair housing for the Black community.

Shirley Green:

I think when they started the Board of Community Relations in the 1960s, I think the one thing... and it's still the case today, whatever version there is of it now is that they were just trying to improve the racial climate, and making sure that the city was doing the right thing by different minority communities within the city of Toledo. I think for the most part though, the issues that were still pressing in the 1960s in Toledo for African-Americans were the issue of jobs and the issue of fair housing. Those are the major pillars that Mrs. Stewart and others on the board were trying to fix.

Ella P. Stewart:

We worked for years before and worked for trying to get people jobs, more or less it was getting people work and locating them... where they could live. We'd take them out... go out here where they had the boxcars, they were sleeping in boxcars out here on Hill Avenue and places. Well, we'd go out and bring them in when we find... the kids look forward to do it.

Shirley Green:

That's hard because now you have to deal with private industries, private businesses. As a city, you can say, "We're going to hire more of this." It's going to be difficult to pressure private corporations to do the same thing, which is why I believe one of the reasons that Mrs. Stewart worked behind the scenes.

Nick Pavlik:

Despite these challenges, the board enjoyed its share of victories throughout the 1960s, one of which was the employment of Black nurses at local hospitals.

Ella P. Stewart: