International relations under the microscope

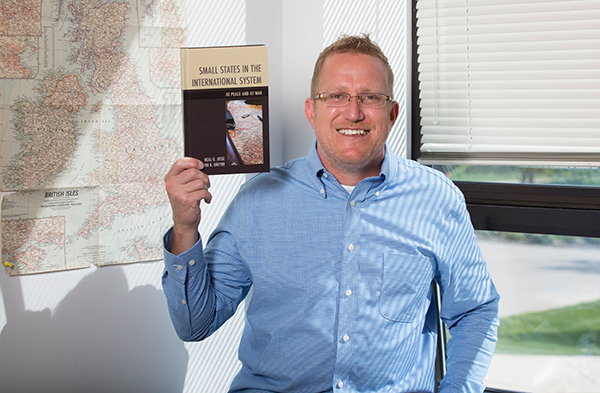

In matters of international relations, size matters, according to Drs. Neal Jesse, political science, and John Dreyer, an associate professor of political science at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology and BGSU alumnus. They are the authors of a new book on comparative foreign policy titled “Small States in the International System: At Peace and at War,” published by Lexington Books.

Although the importance of the relative size of the players in international relations might seem obvious, Jesse and Dreyer’s research shows that both historically and today, large states like the U.S. and Russia tend to make foreign policy decisions based on the realist theory, which assumes that the smaller states they are dealing with are just like them — only smaller — and will react as they would.

Except that they don’t. Jesse and Dreyer expose the limits of the prevailing theory by demonstrating that small states only act in keeping with realism when threatened by states close to their own size. When they are threatened by much larger states, factors such as the sense of national identity and who is in power at the moment will determine their response.

“Small States in the International System” is the first book to test and compare the three major International relations theories about how states behave, using small states as case studies. It looks at the realist theory, the social constructivist theory (which concerns establishing and defending norms and identity) and the domestic/liberal theory (which holds that foreign policy will be based on who is in power at a given time) and applies them to conflicts in and among Ireland, Switzerland, Finland, Vietnam, China, Ethiopia, Somalia, Bolivia and Paraguay, from 150 years ago to the present.

The authors took a scientific approach to their studies. They established clear, testable hypotheses and expectations for each of the three theories and then tested the case studies against them. Dreyer, an expert in military history, provided the descriptions of wars and the historical fact that supplied evidence toward the theoretical concepts. A table in the final chapter shows which hypotheses were supported.

The results help explain why the tiny Finland, for example, when threatened by the Soviet Union in the second world war, steadfastly refused to accede to Stalin’s relatively minor demands for territory in his attempt to hold off a German invasion of the Soviet Union’s northern border. The dominant realist theory would predict that Finland would either seek alliance partners, known as “balancing,” or give in to the much larger Soviet Union’s demands, called “bandwagoning.” It did neither of those, in spite of the fact that it was clear that if the Soviet Union wanted to overrun Finland, it could easily do so at any time.

Rather than cooperate, the Finns decided it was better to maintain Finnish identity as resistors than give in to Stalin, Jesse said.

“One of the things we found in this book is that since smaller countries don’t control their own destinies — because if a large country wants to be belligerent with them, it’s going to be — they’re not as concerned about winning that conflict,” Jesse said.

“What they can do is influence what the post-conflict world will look like by establishing what the opinion would be of them postwar. Finland resisted, and the international community recognized the Finnish resistance as brave, noble and honorable.”

This reinforcing of one’s identity aligns with the social constructivist theory, and is also seen in Ireland and Switzerland’s absolute dedication to maintaining neutrality, no matter what the situation or who is in power. This is what keeps them from joining NATO, or in the case of Switzerland, the European Union, even though that might be to their benefit, Jesse said.

Self-conception plays another part in how states position themselves for the post-conflict landscape, Jesse said. Even in the event of a world war, the U.S., China and Russia are not afraid of themselves disappearing. But, as Eastern Europe has seen multiple times, smaller states have indeed been subsumed into others as a result of conflicts.

“Smaller states tend to be nations of people, with an ethnic identity,” Jesse said. “Their position has always been tenuous in relation to big powers. Lithuania may not survive, but Lithuanians will. They feel ‘Even if our state comes and goes, we want to pursue policies that preserve us as a people, so that after this war, we will be in a position where our state can come back, and even if violence is inflicted upon us, we must come out on the other side.’”

Conversely, when larger states are directly threatened, they think in power calculations, Jesse said. “They think, ‘Am I powerful enough to defeat this country? Are they powerful enough to defeat me? Do I need other people to help me defeat this country?’”

Those countries will then either “balance” against the threat by arming themselves and seeking allies, or “bandwagon,” by joining with the threatening state.

But small countries don’t do that.

“Our theories are often built on how large countries behave,” Jesse said. “According to the realism theory, states react mainly to power and the structure of the international system, and it assumes all states are the same, no matter who’s in them. But when it comes to predicting how small states will react to actions of much larger states, of the three major theories, realism is probably the worst.”

So why do government policy makers continue to operate utilizing the realist theory in the face of historical evidence that it is not actually realistic? The authors say that realism is so dominant that it’s hard to find anyone who doesn’t believe in it, and that when a situation doesn’t work out as expected, they “rationalize it backward to make it fit the theory,” Jesse said.

Government leaders in foreign policy also tend to lag behind theories by a certain amount of time, Jesse said, so it is the hope of the researchers that by sharing their theoretical contributions through publishing, presenting and teaching they may influence next generation of policy makers.

Jesse’s next book will build a new theory as to why realism doesn’t predict item actions of small states well. At this time, the working title is “Theory of International Relations: State-centric and Nation-centric Approaches.”

The two authors have collaborated before. They met when Dreyer was a graduate student of Jesse’s at BGSU, where he earned a master’s degree in public administration. Dreyer later contributed a chapter to Jesse’s previous book, “Beyond Great Powers and Hegemons: Why Secondary States Support, Follow or Challenge,” co-authored with Drs. Kristen Williams and Steven Lobell.

Updated: 12/02/2017 12:36AM