Exercise could speed wound healing in diabetics

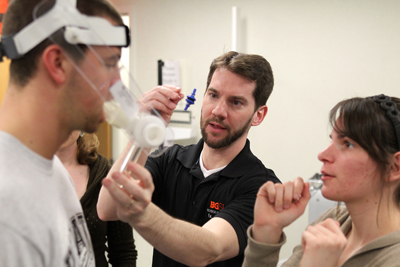

Dr. Todd Keylock (center) helps student Kevin Radabaugh prepare to take the VO2 Max test, which measures one’s fitness level, while student Lauren McCartney looks on.

BOWLING GREEN, O.—There’s just no getting around it. “We were designed to move and when we don’t, we experience all sorts of problems,” says Dr. Todd Keylock, an assistant professor of exercise science in Bowling Green State University’s School of Human Movement, Sport and Leisure Studies.

Keylock is researching the connection between exercise and the immune system and, specifically, whether activity can improve wound healing in diabetics. Healing is slowed by chronic inflammation, and if exercise can reduce or prevent that inflammation, serious problems may be averted, Keylock said.

Because of its connection to skin health, Keylock’s research has been reported in Allure magazine, Health, Dermatology Times, The Journal of the American Medical Association and other publications.

Diabetes rates are soaring in the United States as people are increasingly sedentary and obese. In fact, Keylock said, what used to be known as adult onset diabetes is now frequently being seen in children due to their being overweight. According to National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse figures for 2007, estimated diabetes costs in the U.S. totaled $174 billion in medical costs, disability, work loss and premature mortality.

One of the dangers posed by the disease is slower healing of wounds, which can lead to infection and even loss of limbs. Here’s where movement comes in. In addition to the well-known benefits of exercise—increased flexibility, heart health—Keylock suspects that physical activity also plays an important role in preventing and reducing chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation has been shown to be a major culprit in a number of illnesses, from heart disease to Alzheimer’s, cancer and HIV-AIDS, in addition to diabetes.

While inflammation is a healthy response to infection or even a splinter—a process in which the body signals the brain to send immune cells to the trouble spot to fend off the invader—“when inflammation gets too high and becomes a chronic condition, damage to the body occurs,” Keylock said.

Keylock is testing his wound theory in the laboratory. One indicator of inflammation is high levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the blood. Keylock is measuring CRP in people with high and low levels of activity as well as inflammation levels in wounds in diabetic laboratory animals, comparing those levels in the inactive to the active animals.

“While the mechanism by which activity reduces inflammation is as yet unclear, there is a growing body of evidence that it does,” he said.

“Although drugs can help reduce inflammation, pills are a less than ideal way of solving the problem. We think regular, aerobic exercise can maintain and restore health by reducing chronic inflammation.” It is already known that regular exercise can help keep blood glucose levels down, another indicator of its importance to health, he added.

However, in the case of diabetes, exercise alone cannot solve all the problems. “It has to be a combination of lowered calories and exercise to achieve weight loss. Exercise scientists know we can’t do this alone,” he said.

Keylock wants to get people moving across their lifespan since higher inflammation naturally occurs with aging. “I try to spread that passion to my students,” he said.

###

(Posted April 06, 2011 )

Updated: 12/02/2017 01:03AM