Ashley Meehan's summer research project

College of Health and Human Services Student Research Award

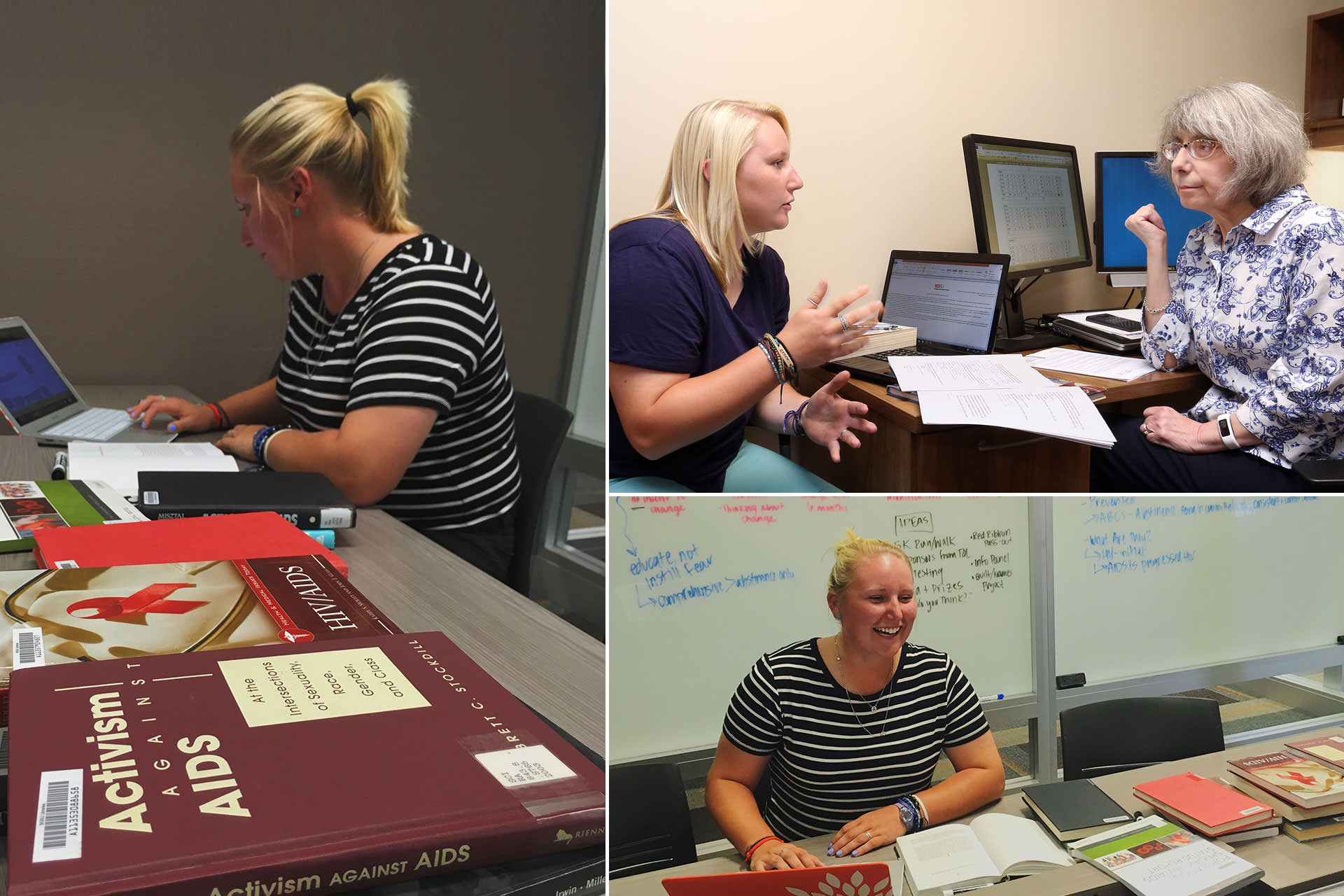

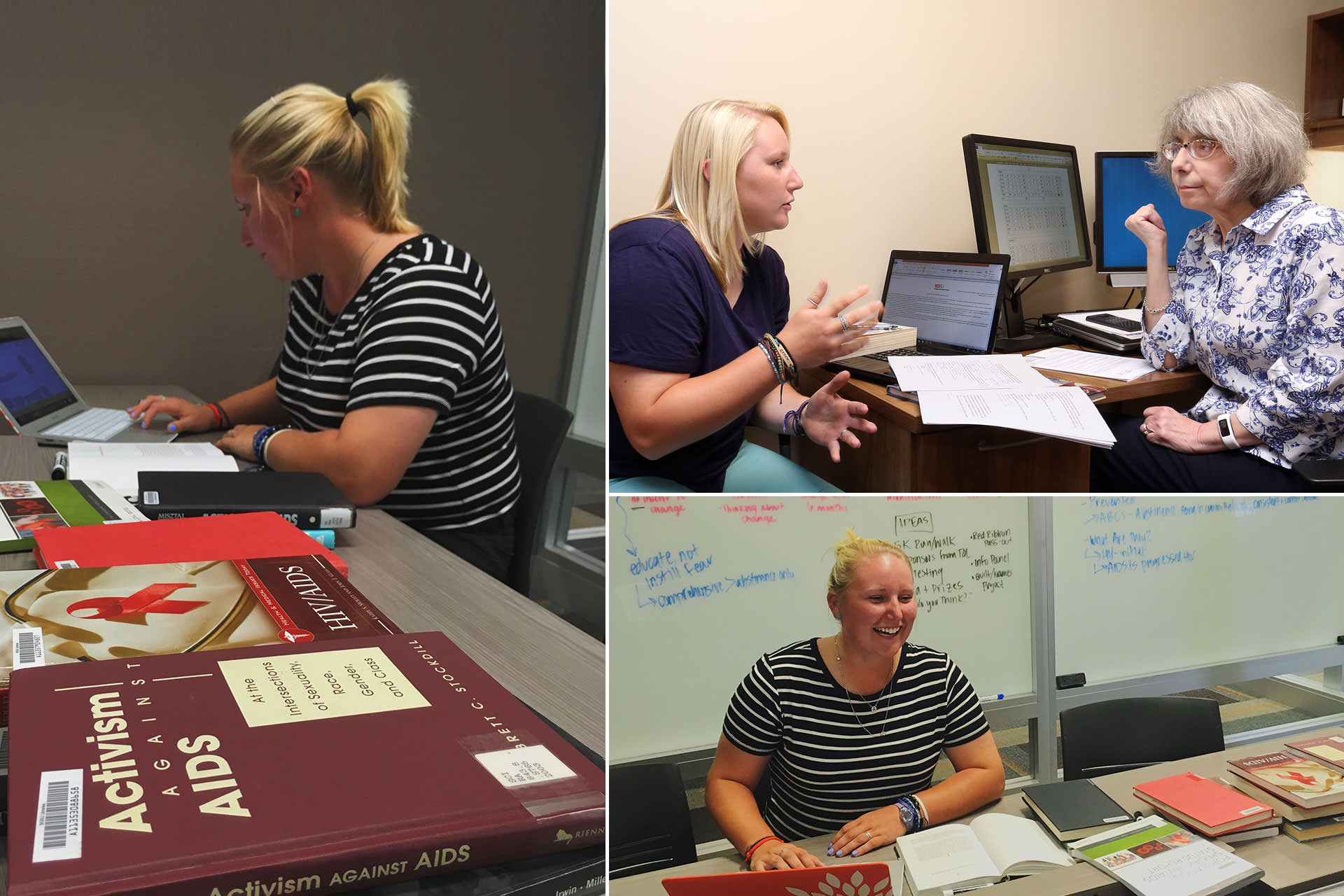

Funded by the College of Health and Human Services Student Research Award, I held focus groups during the summer to gather how students felt about HIV and AIDS — about the disease itself, the hope for eradicating the disease, and how we can make a difference at Bowling Green State University. I also spent a majority of the summer digging through 35 years’ worth of literature about the disease, which has had a wide range of names and stigmas since it was first identified in the United States in 1981.

HIV and AIDS usually feel quite distant to most people. They don’t have it, nobody in their immediate circles have it and it isn’t talked about as much as it used to be. Even I, as a 20-something-year-old with seemingly endless access to health-related information and a family member who had passed away from the disease, didn’t know more than the basics of transmission — by contact with bodily fluids through sex, needle sharing, birth or breastfeeding.

After serving in an HIV orphanage in Guatemala during my sophomore year at BGSU, I was empowered to act. I returned to Bowling Green and began to question how HIV and AIDS were being addressed at BGSU. I took courses in the Department of Public and Allied Health that began giving me the tools to help meet the need I saw on campus.

I had never held a focus group where a group of 5-8 individuals gather for a conversation or group interview about a topic to collect baseline data and identify health-related needs in a community, but through my courses in Public Health I felt familiar with the concept. With the help of my encouraging professor and mentor, Dr. Rebecca Fallon, assistant professor in public and allied health, I was able to hold focus groups on campus with BGSU students to discuss HIV and AIDS. The focus groups gave me an idea of what typical students thought, felt, and knew about HIV and AIDS. We discussed which groups of people are at a higher risk for contracting HIV (men who have sex with men, African-Americans, those living in poverty, and IV drug users), how long an individual can expect to live with HIV (10-12 years without medication, and up to 70 years with medication), and about potential treatments (many individuals affected by HIV take multiple medications every day to keep the virus in check).

Searching through scientific literature is not glamorous. Trying to convince people to voluntarily talk about a disease that is ignored and sometimes uncomfortable is even less glamorous. But, one theme I’ve noticed all along is that education is necessary. Publication after publication, education about HIV and AIDS, whether among the young, elderly, minorities, majorities, rich and poor, continues to prove mandatory for not only erasing the stigmas around the disease, but also for slowly erasing the number of those affected by it.

Our campus has great resources for HIV and AIDS: our Wellness Connection offers free HIV testing, and our Falcon Health Center has a talented team of medical professionals on hand.

Even after 35 years, new cases of HIV are still being diagnosed, and existing cases of HIV and AIDS are only being managed instead of cured. This year, I will use the information collected from my summer research to plan our campus’s first ever AIDS Awareness Week, which will include a variety of educational programs and activities to get people talking about the disease and the ABC’s of HIV prevention — abstinence, being in a mutually monogamous committed relationship where both partners are negative, and correct and consistent condom usage.

I do not anticipate that I will be the one to find a cure for HIV and AIDS, but I do anticipate continuing to be a part of the cure to the lack of education about HIV and AIDS wherever I go.

Updated: 03/15/2025 01:50AM